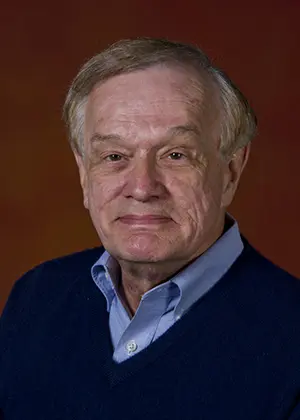

My Mentor, Jim

My last email exchange with Jim Chesebro was in June 2019. He had sent me a note of congratulations about an article I had written. In that note he mentioned that he had recently retired. No way! This couldn’t be. Not Jim. Not with his relentless energy, his infectious joie de vivre, his passion to find meaning in the ordinary and demystify the momentous.

Jim was, in a word, brilliant. He was a prolific scholar, a dedicated teacher, and a visionary. He was also a person of immense integrity, fiercely loyal to his students, colleagues, and friends. And he was so devoted to his husband, Don. They had been together for 38 years and married in 2013, and Jim always spoke so lovingly of him.

Jim was full of life! The wattage spiked when he entered a room. You soaked in his every word. And when you spoke, he listened. You felt connected to him, respected by him.

Sadly, I just learned that Jim had passed away. He died three years ago, just a few months after our final exchange. It’s heartbreaking to think that he is no longer with us. He had more of an influence on me than he will ever know.

Jim was my doctoral advisor in graduate school. I met him in the late 1970s when I was just 22 and starting graduate school at Temple University in Philadelphia. The program was rich in professorial talent, and Jim, although only in his early thirties, was already quite accomplished. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota a few years earlier, and by the time I met him he had written two of the several books he would eventually author as well as dozens of what would amount to hundreds of journal articles, book chapters, and presentations at professional conferences.

I was intrigued by Jim right from the start. My interest was spurred by his work in popular culture, one of his areas of expertise and something new to me. With compelling insight, Jim demonstrated how the TV shows and movies we watch, the music we listen to, and the art we admire help us to understand society in the broader sense. He showed how they can help us forecast the arc of trends, like which groups will gain political and economic influence and which were likely to be weakened.

Jim also studied how disenfranchised groups found avenues for their voices. In one of his classes, he used graffiti as an example. In the 1970s, graffiti became a ubiquitous feature of city landscapes. Viewed by many as visual vandalism, graffiti was decried in editorials as an encroachment on the municipal environment, a reflection of and contributor to urban blight.

Jim interpreted graffiti as an expression of powerlessness, a statement of defiance in the public square, couched in artistic expression. At the same time that it was anonymous, it had signature styles and, accordingly, had elements of both furtiveness and openness.

Jim could look at such things to gain insight into larger societal tensions as well as for the inevitable futility of “cracking down” as a solution. He reasoned that such a strategy would prove counterproductive, intensifying the very victimization that sparked graffiti. Jim didn’t advocate for defacement. But that wasn’t his point. Instead, it was to explain how powerlessness can manifest symbolically and that you can keep people down only for so long.

I really got to know Jim through the process of writing my dissertation. We had standing meetings to frame the project and discuss progress, typically in his office after one of our classes. Offices reflect the personality of their inhabitants. Jim’s was neat and orderly but filled with stacks of the manuscripts he was working on. Occasionally, we’d chat over dinner in a Center City restaurant. Jim generously gave me all the time I needed.

My doctoral dissertation examined the influence of neighborhoods on their residents. With a rich history of fixed neighborhoods – Italians, Jews, Irish, Blacks, Hispanics, as well as an array of other nationalities and ethnicities – Philadelphia was like a sociological Petrie dish, fertile ground for exploring how neighborhoods shaped and reinforced the attitudes and behavior of their inhabitants.

I chose a white working-class Northeast Philadelphia suburb as a case study. What became glaringly clear early on was the community’s belief that the world was changing in ways that were unfavorable to them. They had become convinced that the American Dream of upward mobility, which they saw as a birthright, was slipping away. In their view, such opportunity was shifting to other groups, notably Black and Hispanic, whom they felt deserved basic civil rights but not the same ticket to middle class comfort they had become convinced was being pried from their grasp.

The term Jim and I chose to characterize their communication was lament. Residents may have whined about their plight, but there was no discussion about mobilizing for action. Instead, it was more like they were in mourning, in this case over the loss of expectations. They were especially distraught over what they regarded as an entrenched aimlessness in their kids’ generation, and they were despondent over their heavy drinking and drug use. To them, it was indolence to excess, a distressing harbinger of a future of diminished hope and loss of stature in society’s pecking order.

Lament was different from the powerlessness that revealed itself in the graffiti. Instead, it was powerlessness with a thick overlay of hopelessness. At the time, around 1980, the only tangible action that the residents openly discussed was how to keep families who were not white from moving into the community. The xenophobia was palpable. It was overt and ugly, racist in tone, with the N-word sprinkled generously into conversations about whom should be excluded from the neighborhood.

In our many discussions about my research, Jim described lament as a seed for resentment. That is, if the perception takes root that society’s benefits are becoming more available to other groups, especially groups they considered unworthy, lament will germinate and sprout into grievance. It would be, as Jim understood, an inevitable progression. Whereas lament is self-directed (“woe is me”), grievance, the next stage, is other-directed (“look what they are taking from me”).

And grievance would show itself in political action, expressing itself in support of candidates advocating exclusion, demanding a return of what they believe was stolen from them and gifted to undeserving others. As grievance deepens, it can lead to the conviction that society’s institutions, for example, the legal system and elections, cannot be trusted, and matters are best taken into their own hands.

Grievance, Jim argued, was a powerful motivator. It can, and throughout history has, paved the way for authoritarianism. After all, if the established mechanisms aren’t working to restore what are believed to be rightful claims to one’s place in society, then demolishing those mechanisms, even if it involves breaking laws, would be considered a necessary solution.

Grievance has always been foundational to authoritarianism, which helps explain the appeal of a charismatic leader who promises a return to better days. Jim would not have been surprised by what transpired on January 6, 2021.

Right after graduate school, I began my career in healthcare. My correspondence with Jim lessened, a casualty of our different professions, busy lives, and living in different parts of the country.

But I thought of him more often than our infrequent correspondence would suggest.

For example, just recently, I was consulting with a hospital on its five-year plan. Following a meeting, one of the executives and I were heading down a corridor when we passed a large conference room. The door was open, and we saw groups of nurses huddled around photos of nursing uniforms on poster boards. There must have been 30 different uniform styles – prints, stripes, pastels, bright neon hues.

The executive explained that a recent survey of employees revealed a high level of dissatisfaction. Employees claimed that the hospital’s leadership was not doing enough to support them. They felt overworked and burdened, and more than a few used the term “burnout” to describe their emotional state.

To help, senior management proposed the idea that nurses on each floor choose a distinct uniform style that would be worn by all nursing staff on that floor. This was intended to promote the team spirit that employees complained was lacking.

I found myself channeling my inner Jim. He understood that superficial fixes like this could produce a fleeting rush of exuberance and would ultimately backfire.

He would have cautioned against allowing for such differentiation of uniform to resolve feelings of alienation from the hospital. Instead, it would be advisable to bring nurses together from different patient floors to select a uniform. Such an approach would build bridges across nursing units, not harden beliefs that they are on different teams. And they might choose a basic uniform style for the entire nursing staff with subtle differences for each floor. That way, a nurse assigned to another unit would not feel like an outsider. But the slight differences might also allow for team identity on each floor.

I shared this with the executive team. I also implored them to address the substantive issues leading to burnout. If not, the perfunctory uniform gesture would come across as mere lip service, tokenism that would likely exacerbate the very problem it was designed to resolve. A piece of candy won’t cure malnutrition.

Jim introduced me to looking at things this way, to get a handle on whether the culture of a society, an organization, or even a family dignified the experience of all its members. If employees in a hospital do not feel genuinely respected by those in charge, chances are neither will its patients. And that’s not all that will suffer – so will the bottom line.

Jim was a tremendous and progressive intellectual force. But I also remember laughing a lot with him. He was fun, jovial, and could be playfully mischievous.

Jim saw the potential in students that perhaps they didn’t see in themselves. If he accepted you as an advisee, he would commit to helping you reach your potential. He’d insist on it. He didn’t do it by lecturing. And he was certainly not an enabler. Instead, he challenged you to find the impetus to grow from within. But he’d be there every step of the way, fully devoted, right there beside you.

Jim laid the groundwork for you to set out on a path toward actualizing. In that way, Jim was, in the most meaningful sense of the word, a mentor. What a distinct honor it was to have him in my life, just was it was for all who had the privilege of his guidance and friendship.

I wish I had shared all these thoughts with him. But this was Jim, and since he always struck me as driven mostly by concern for others, especially the marginalized, I suspect he would have waved off such adulation. Time was simply too precious, and there were too many intriguing ideas demanding attention and too many people on society’s edge whose voices could use some amplification.