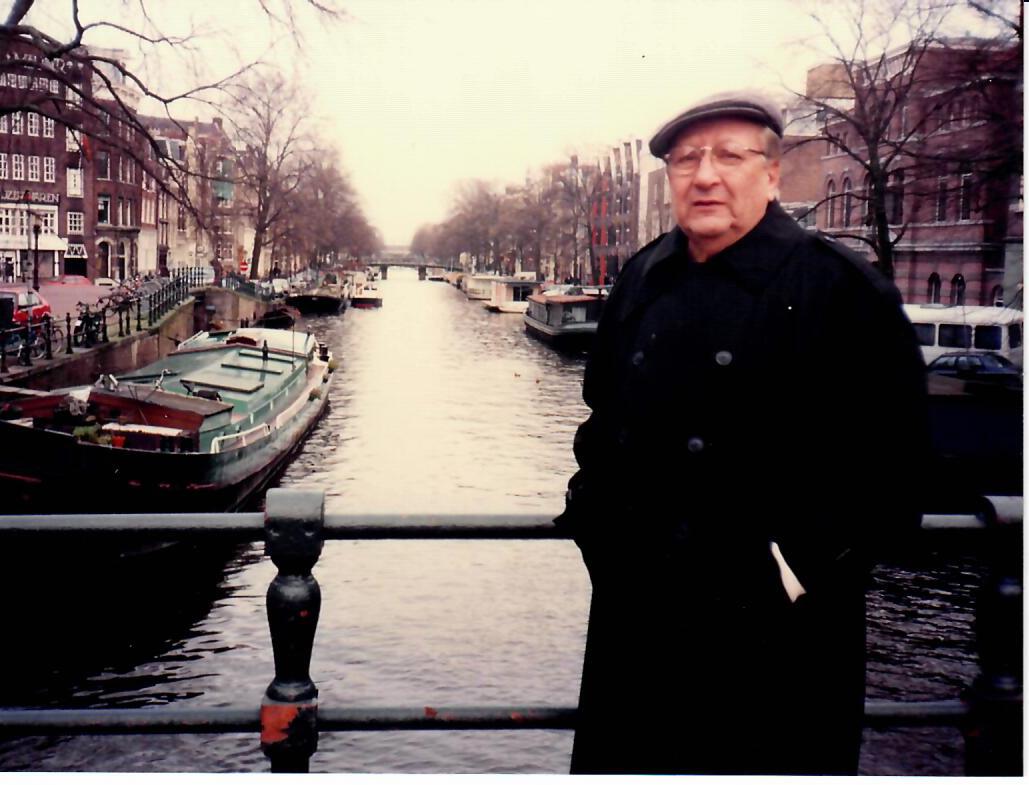

Remembering My Father

Decades ago, my father, George, and I got into a stalemate over an essay I implored him to write. I often reflect on that moment, but especially now as this is a milestone year, the year he would have turned 100. He died eighteen years ago, and I think of him so often. Remembering the impasse over the essay helps me to understand the kind of father he was.

When I was in high school, I took a writing class in which we were asked to compose a short autobiography. I don’t recall what I wrote, but I do remember that my teacher had given me some encouraging comments along with a respectable grade. At the time, I was unaccustomed to confidence-boosting feedback for my writing and, frankly, it never occurred to me to even hope for that. But the supportive words from that teacher motivated me. That was a seminal moment for me – the moment writing ceased to be a chore.

Armed with my ostensibly praiseworthy two-page essay, now adorned with glowing feedback, which, in retrospect, was probably something like, “Nicely written story and no glaring grammatical errors,” I was now well onto the no-turning-back trajectory of becoming the next Hemingway. I shared the good news with my parents. Taking it a step further, I pressed my dad to write about a period in his life. Maybe a brief autobiography, I suggested, since this was my newfound genre of expertise. After all, I now had two pages of proof. His response was, well, let’s just say, unenthusiastic.

My dad’s reaction was frustrating as I was sure that writing the two pages would be a breeze for him. I liked to think my dad was the smartest person I ever knew, and as I got older, the wisest. He was an avid reader with a first-rate intellect and was curious about the world. We always had wonderful conversations, lively and enriching, and back then, the 1970s provided us with rich fodder for political discourse.

Over the course of that week, a clear pattern emerged: I would push him to write and he would resist; I would nag, he would balk. Our positions hardened, the rhythm of our interactions on this topic became quite predictable. He was like the kid who had to be coaxed into practicing the piano, and I was the hovering, hounding parent, insisting that it was for his own good. Oh sure, I could try the punishment route. But where would that get me? What could I do, forbid him from watching his favorite show? Withhold allowance? Take the car keys?

Finally, whether from exhaustion or because we got sidetracked, I stopped pestering. The matter was dropped.

About a week later, I was doing my homework at the kitchen table when in walked my dad. In his hand were three sheets of loose-leaf paper, which he placed in front of me. I was momentarily taken aback, mostly from seeing a pageful of his writing. At that instant, it dawned on me that I had no idea what his handwriting even looked like. I knew his signature, and I knew how some of his written words appeared, like words on a shopping list. In such a format, the words are independent, not linked by an overall aesthetic or flow. But there, on those three pages, was a full portrait of his handwriting. I had never even thought of him as having handwriting. The very concept didn’t apply.

When I focused more closely on those three sheets of paper, my heart skipped a beat. My father had actually done it – he had written a short autobiographical essay!

As I read his words, I began to understand some things about writing and how that relates to other ways we express ourselves. My father could speak excitedly about things he did, like playing stickball as a kid on a busy street in the Bronx, having had to dash between parked cars to dodge oncoming traffic and even the occasional horse and buggy. He could speak wistfully about the wonderfully tantalizing aromas of breads and pastries emanating from local bakeries. And he could speak amusedly about what it was like to sit in a sweltering junior high school classroom in late June, baking in the intense afternoon sun while wearing the requisite long-sleeved shirt and tie. He was a wonderful storyteller, bringing life to his experiences, often injecting humor, even laughing at himself and his foibles.

But none of this came through in his writing. It was void of description. There was no imagery. Just the facts, ma’am, the plot points of his life. “I grew up in the Bronx… My parents spoke little English… My best friend’s name was Bernie…” Writing requires time, patience, and practice. He couldn’t easily translate his memories into this different medium of expression. It had simply never been part of his experience.

I could have followed up with him, cajoling him to add some flavor and develop an idea or two more fully for the next “assignment.” What was it like to be a young child having to act as a translator for your parents? What did you and Bernie talk about?

After all the resistance, I was shocked that my dad had actually made the effort to write something. But more, I was grateful. Above all, it was a loving, confirming gesture. I could tell it wasn’t his first draft: there were no cross-outs, each new paragraph was indented. He had taken his time. I think he wanted me to be proud of him. His apprehension, I came to recognize, was rooted in a worry that I might not be.

I never again asked him to write. There was no need. I did, however, ask him to talk to me and elaborate on the events in his essay. He happily obliged. If he ever decided to pursue writing, it would be because he wanted to. Of course, I suspected he never would. And that was perfectly fine.

I treasured that moment. I treasured it because, more important than the essay, he stepped outside of his comfort zone to make me feel good. Asking him to write more would have transformed a beautiful moment into an expectation that would ultimately serve no purpose other than to diminish that one.

I didn’t fully understand this at the time, but I had a vague sense that sometimes it’s best to end something on a good note. And even though you may want more, nothing will ever approach the sweetness of that good note.