Building Better Lifeboats

The harsh odor hit us like a ton of bricks just as the elevator door opened. I had never experienced anything like it before – an intense hyper-chlorinated sanitizing agent that was intended to neutralize the rankness of the hospital air, but instead the effect was compounded, burning my throat and eyes. I was there with Kevin, a fellow student whose eyes were also tearing up. Our escort, a facility manager, said quite straightforwardly, “You get used to it.”

That was over forty years ago. Kevin and I were in a doctoral program at Temple University, and this was our first day of a two-week research internship project at The Philadelphia State Hospital at Byberry, a psychiatric hospital, or mental institution as places like this were called at the time. Not long before, they were called insane asylums.

Certainly, the world has changed since then in terms of how we think about and treat mental health conditions. But the more I read about the considerable upswing in mental health issues today, something from that experience in the late 1970’s feels eerily familiar.

considerable upswing in mental health issues today, something from that experience in the late 1970’s feels eerily familiar.

Byberry, located in a suburb of Philadelphia, was very large, comprised of multiple buildings spread across its multi-acre campus. It had opened in 1911, a response to overcrowded conditions in another nearby institution. Byberry steadily grew, eventually housing approximately 7,000 patients by the 1960s.

Barbed wire surrounded the campus. An armed guard checked our IDs at the gate. It was quite foreboding, and it felt more like we were entering a platoon encampment in a war zone rather than a place supposedly in existence to care for people.

The hospital’s internship liaison met us at the entrance to the building in which the geriatric ward was located. We were assigned to this ward because, as she explained in a matter-of-fact tone, the geriatric patients were the “tamest,” and we were less likely to be targets of violence with that group. Kevin and I shared that eye contact moment that says, “What have we gotten ourselves into?”

Pointing toward the elevator, the liaison mentioned that a facility manager would meet us when we arrived on the second floor. And there she was, waiting for us as we as gagged even before the elevator doors fully opened.

As we walked down the long corridor from the elevator to the locked geriatric ward, we passed a patient on a wooden bench. He was in a straitjacket, wailing incomprehensibly toward the wall behind him. As we got closer, we saw that he was tethered to the bench with a bedsheet. I couldn’t tell if the man was thirty or sixty years old as his facial contortions obscured the physical markers that we rely on to get a sense of one’s age. The straitjacket was stained, and we weren’t sure if it was food, blood, or a mix of that plus more. He had a large bruise on his forehead.

As we passed him, I asked the manager if he was okay and if he was in that straitjacket all the time.

“Only when he acts out,” she replied, never bothering to look at the man, as though he didn’t exist.

“How often does that happen?” Kevin asked.

“A couple of times a week, at least,” she responded, with an indifference that seemed jarringly at odds with the fact that a human being was being restrained this way.

It was all so new to us. I couldn’t decide what was more shocking, seeing a person bound like that or the manager’s apparent disinterest. I thought maybe this was her way of coping, that getting through the day required embracing the illusion that his suffering didn’t exist. Or maybe to her he wasn’t even a real person.

The manager had a large key ring hanging from her belt, from which about fifteen keys dangled, rhythmically ding, ding, dinging as they slapped against her hip as she walked. You come to know that sound in this place. It’s the sound of authority, a symbol that says, “I’m in charge,” like a sheriff’s badge. The manager said that we were heading into the Day Room, where the patients would be watching TV.

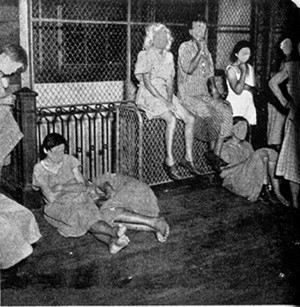

She deftly chose one key from the ring and unlocked the heavy steel door. The Day Room was spacious, at least 50 feet by 75 feet. Wooden chairs and small benches and a few plastic couches dotted the space. The drab linoleum flooring matched the muted mint green tones of the walls. The ambiance felt industrial, more suited to antiseptic maintenance than to patient comfort. On adjacent walls hung two television sets, each blaring out a different soap opera.

There were about 45 or 50 patients in this space. Most noticeable was that no one was speaking to anyone else. The majority were facing one of the TVs, though they didn’t seem to be paying attention. Their gaze didn’t change during commercials. It was all just vacant staring. Kevin and I again shared that “look.”

The women wore institution-issue light-colored robes. The men wore pajamas. At once, we understood the origin of the odor we encountered upon exiting the elevator – it was evident from the matted hair and body odor that hygiene was not much of a priority.

The facility manager brought us to meet Mr. Spivey, one of the ward managers. He had a wiry frame and a penchant for hunching forward. I remember his blue plastic pocket protector which had five or six pens protruding from the top.

He took us into his office, a small nondescript room with a window facing the Day Room. Every surface was piled high with papers and patient charts – the floor, his desk, a small table that was missing a leg, and the two guest chairs. We stood on a tiny, uncluttered island while he addressed us.

Mr. Spivey curtly announced that he didn’t have time to provide an orientation. Quickly getting to heart of the matter, he said, with a sort of laugh, “I suppose you fellas are keeping a journal for your class. Just don’t write anything negative about us.”

We weren’t sure whether it was a joke or a warning. It might have been a little of both, but at this point, after just a few minutes in the facility, the glaring lack of humanity that pervaded this place led us to conclude it was definitely not a joke.

As Mr. Spivey’s smile abruptly faded, he picked up a few files and ushered us toward the door. Pausing a moment, he said, “Hey, listen, I gotta be honest with you. I don’t like having interns here. But it wasn’t my call. I just do what I’m told. But the last time we had interns, they agitated the patients. And we had to double their meds. Which comes outta my budget. Administration brings the interns in and I gotta pay for it. Then they kick my butt because we’re spending too much. It’s nuts! So, listen fellas, go easy with the patients. If you talk to them, don’t rile ‘em up.”

Message received.

“Why are these patients here?” I asked as Mr. Spivey started to head out of the office. “Do they all have a similar diagnosis?”

He turned back to us. “They’re here because they’re crazy,” Mr. Spivey replied, with a raised eyebrow as though he had just heard the stupidest question. Then he said, “The clinical term is ‘undifferentiated schizophrenia.’”

Kevin jumped in, “We’re taking social psychology classes. I never heard that term before. What does it mean?”

Mr. Spivey stared at us through squinted eyes, seeming to debate with himself about how to answer. “Fellas, I’m gonna be straight with you,” he began. His tone suggested he wasn’t as much interested in informing us as much as he was losing patience with another set of nuisance interns, especially curious ones.

“We use that term ‘undifferentiated schizophrenia’ when it really doesn’t pay to go through a whole expensive diagnosis. The patients are just too far gone. And a complete workup costs money we don’t have. Besides, they just want to sit around all day. You go to some of the other wards where the patients are younger and prone to violence – that’s a whole different ballgame. Here, they’re just riding out their time. So, it’s a lot easier, as long as they take their meds. And as long as no one riles ‘em up.”

Did he just say that the patients are too far gone? Really? Human beings not worthy of a more rigorous evaluation? This wasn’t behavioral health. It was behavior control. “Undifferentiated schizophrenia” was nothing more than a catchall phrase, but it carried the distinction of devaluing patients who did not merit more diagnostic attention.

It became clear: This wasn’t a hospital. It was a warehouse, a citadel of soullessness that robs patients of their consciousness and staff of their conscience.

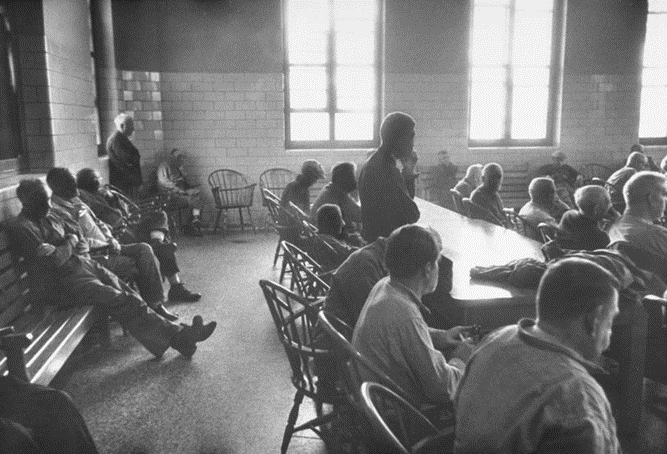

We were permitted to observe a weekly group therapy session consisting of ten patients. The staff called it prodromal therapy. We never heard that term, and when we read about it later we learned that prodromal therapy was for people in early phases of schizophrenia. This didn’t compute for us since most of the patients had been there for a long time and had largely stabilized. Then again, much of what we observed didn’t make sense to us.

The therapy session was held on another floor in a room that was musty, damp, poorly lit, and very chilly. The patients sat in a circle along with a staff member who was the facilitator. We didn’t know his name or his role. This was par for the course since no one wore name badges or introduced themselves. We sat off to the side.

The facilitator asked questions such as who the current president was and what the current day was. None of the patients could answer. Most sat with blank stares. After a few minutes, one patient asked if today was grilled cheese day.

About twenty minutes in, the facilitator told the group that it was about time to wrap up. As he did, he lifted a patient chart from the pile in front of him and checked off the box marked “No Progress.” It took under a minute to repeat this for all ten charts.

As we stood to leave, Kevin and I asked if there ever is “progress.”

“Progress!” he guffawed. He explained that updating the record was required for funding by a state agency. “It’s all a game,” he said straightening the stack of charts, “You just have to learn how to play it.”

The facilitator escorted the patients back to the Day Room. They took the seats they were accustomed to sitting in and resumed their usual practice of watching TV or just staring aimlessly. This was all so astonishing to Kevin and to me, seeing lives reduced to sheer idleness and stagnation.

On our next visit, we asked Mr. Spivey if we could interview the patients for our project. He said, “You fellas can do whatever you want, but remember, don’t get ‘em riled.”

Mr. Spivey didn’t even ask what questions we were going to pose. How could they not want to know what we were going to ask the patients? After all, weren’t he and his colleagues responsible for the patients’ welfare?

Kevin and I compiled a list of twenty questions for the interviews, like about the patients’ families, the work they did before they came to the hospital, books they enjoyed, favorite TV shows, and views of politics.

After observing the patients in the therapy session, we anticipated that they would not be able to answer any of our questions. We had assumed that this would be due to their mental condition or that the medication dulled their awareness. Or both.

However, we forged ahead. Over the course of two weeks, one at a time, the patients joined us in a small conference room adjacent to the Day Room. This room had cushioned chairs, making it a relatively comfortable setting in which to speak with the patients.

What happened in our interviews astonished us! With just a few exceptions, the patients spoke with clarity and coherence about most of the topics we raised.

One patient, Mary, described her 20-year marriage to Freddy, recalling how painful it was when he was diagnosed with cancer and eventually died. That was about 10 years prior. She explained that her depression was so deep that she couldn’t sleep for more than two hours at a time. While describing all this, her affect was neutral, colorless, as though she was reading a script with no feeling. The juxtaposition of Mary’s expressionlessness and her heartrending story was disconcerting.

Mary went on, divulging that she started taking sleeping pills. Her sister was worried that she was taking too many and was at risk of overdosing, so she contacted a psychiatric hospital (not Byberry). Mary was hospitalized for a few weeks, diagnosed with depression and anxiety. “That’s what they called it,” she said. “But I was just so lonely. So lonely.”

A month after discharge, she took thirty sleeping pills and was found unconscious by her sister. “One thing led to another,” Mary said, “and here I am.” She looked away for a minute and sighed, with just a hint of affect.

“You do get used to it,” she continued. “I like watching TV.”

“What’s your favorite show?” we asked.

“Whatever they put on.”

Mike, another patient we spoke with, was a WWII veteran. He told us he was a cook in the Army, but while never directly on the front line, he was usually just a mile or two behind it. Fighter planes raced overhead, so low he could see the faces of the pilots. The bombing raids were intense, explosively loud. The kitchen patrol guys – Mike called them "KP" – all suffered from ringing in their ears. The ringing persisted after his discharge. After a while, he couldn't tell if the noise was imaginary or real, but a couple of years later it started to sound like machine gun fire. He heard it every night. It became deafening. One night it was insanely loud, and he hid under his bed. From then on, he did this night after night. He was afraid to tell anyone because he thought he would lose his job as an auto mechanic. Sleep was getting more and more elusive and Mike missed a lot of work, eventually getting fired.

One day, a car backfired on Broad Street in Center City. Mike dropped to the ground waiting for the “gunfire” to cease. Finally, convinced it was safe, he looked up into the faces of two police officers. He was taken to a mental hospital for observation but was soon released. His money ran out and Mike became homeless. He lost track of how long he was at Byberry but guessed it has been at least ten years.

Kevin and I thought that Mike was in his 90’s – his gray eyes were sunken into deeply gaunt sockets, his limbs were so frail we thought they could break at any moment, and his skin was wizened and ashen. We were shocked to learn he was only fifty-seven.

As we were finishing our interview, Mike said, “It’s easier to be here than out there," adding, as he pointed to a windowless wall. “It was all so hopeless.”

In those days, we did not recognize PTSD as we do now, after the war in Viet Nam shed more light on this tragic syndrome.

Overall, we interviewed about 25 patients. The stories we heard were so different, yet so similar – different in life circumstances, but similar in a need to be relieved of the pain, of not feeling heard or understood, of loneliness, of torment. We heard about lives filled with despair that reached depths we had not been prepared to hear.

Many spoke fondly about husbands and wives, children, brothers and sisters, and parents. Several did share that they had serious problems with some family members, including broken relationships or long-standing animosities. One man hadn’t spoken to his brother in the 50 years since the day he accused him of stealing $10 from him.

To us, the majority seemed, well, reasonable, at least in a way that wouldn’t have led them to this hellhole. All appeared shy and withdrawn, and we chalked that up mostly to the drugs.

But it was the loneliness that came through over and over, with an overpowering intensity greater than the germ-destroying scrubbing agents. But there was no such agent that could completely scrub memories clouded with the pain of desolation. For some, even a lifetime of being with others, of being far from alone, couldn’t derail the feeling of being trapped by isolation.

For each, at some point, the burden of what they were carrying inside broke them.

Not one patient – not one – suggested they would prefer to be elsewhere. Kevin and I came to see this as the great tradeoff. Byberry patients gave up their agency, their independence, their very personhood in exchange for being free of the pain. Byberry is where you go when you hit rock bottom and going up is impossible, when resignation envelops you and any sliver of hope has long since evaporated.

As sad as it was to hear the stories, it was heartbreaking to hear them expressed so unemotionally, without even a hint of spirit or trace of passion. The only thing left to care about in Byberry was whether it was grilled cheese day. This should not be the bargain that Mary or Mike should be forced to make. I couldn’t help but think that we – all of us, collectively, as a society – had failed them.

The drugs the patients took would not “fix” them. That wasn’t even the purpose. They were designed for disabling, not helping – psychotropic artillery intended to benefit the staff, not the patients, like a tranquilizer dart to fell a wild animal before it rampaged out of control.

This whole Byberry experience had come back to me a few weeks ago. I was packing some boxes in preparation for our move, and I found the spiral notebook I’d used for that internship. I mentioned it to one of my students at SUNY, a hospital administrator. She instantly related and shared a story about a fifteen-year-old who had just been released from her hospital. The administrator called her “Jen” to protect her privacy, so I’ll do the same.

A high school sophomore, Jen had taken a bottleful of her mother’s sleeping pills in a desperate attempt to end her life, to get rid of a pain that had become too torturous to bear. Her mother found Jen lying unconscious in her bedroom and immediately called 911. She was taken to the Emergency Department in my student’s hospital. Fortunately, Jen survived, with no neurological or other long-term damage.

Desperate to get insight, while Jen was hospitalized her mother looked through Jen’s phone and discovered hundreds of texts between Jen and her long-time best friend, Sarah. Apparently, both young women were eager to be welcomed into the “popular” group. Sarah was accepted, but Jen was not. At first, Sarah pushed to have Jen included, but pushing too hard would have risked her own acceptance.

Sarah confessed to being under immense pressure from being caught in the middle. She texted that the other girls were insisting that Sarah call off her friendship with Jen altogether. Sarah turned her back on Jen, not only abandoning her but eventually joining the others in ostracizing and harassing her.

Jen texted Sarah over and over that she was “losing it,” that life had become “hopeless,” and that she “can’t live this way anymore.” Sarah ignored her pleas.

We all know that, sadly, Jen’s story is far from unique. The national statistics are alarming. A recent study reported that a jaw-dropping 44% of teenagers have “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness.” And polls indicate that our optimism about the future is at the lowest it’s been in over 30 years.

Over the years, we’ve come a long way in advancing our understanding of mental health and destigmatizing those suffering. And advances in psychopharmacology have been a blessing for millions, making it possible to manage symptoms that would otherwise be exceedingly distressing.

But we have not done enough to address the scourge of loneliness and hopelessness, the evil twins that have played a role in landing many of those patients in Byberry. While it would be unfairly reductive to hold loneliness and hopelessness as singularly responsible, it would be equally unfair to dismiss them in light of what the patients shared.

And those demons are still with us, burdens that more and more people carry inside, bringing so many today to a breaking point.

Loneliness is a complex matter. For young people, peer pressure and the need to conform to social and physical ideals can give rise to a disconnect between the identity projected outward and a private self that may be doubt-ridden. Feeling forced to present one narrative about yourself when the real story is quite different is a gap that, for some, is excruciating. The loneliness doesn’t disappear when you are not alone. In fact, for many it’s worse – trying to fit in when your self-confidence is depleted, coming to believe that hope will be forever elusive.

and a private self that may be doubt-ridden. Feeling forced to present one narrative about yourself when the real story is quite different is a gap that, for some, is excruciating. The loneliness doesn’t disappear when you are not alone. In fact, for many it’s worse – trying to fit in when your self-confidence is depleted, coming to believe that hope will be forever elusive.

We may easily point to social media as the culprit, but we have yet to gain a good understanding of why vulnerabilities are more pronounced in some than in others. And with young people, restricting social media engagement is not without consequence as it can prompt feelings of exclusion. Perhaps it is more important to ask if one were to be deprived of social media, how would their time be filled in a more meaningful and positive way. For many families, that’s the trickier side of the equation.

Today, as I look back at my experience at Byberry, I struggle to understand if and how things have really evolved. In the decades since, we have made great strides in humanizing behavioral health and have rendered unthinkable those cruel, barbaric warehouses. Large-scale closings of those places began in the 1980s. Byberry itself was shut down in 1990.

Yet, one of the chief shortcomings of our healthcare system is that it is set up largely to address illness and injury once they occur, not to prevent them. But it’s not enough to ensure compassion and good quality therapeutic attention when a behavioral health issue arises. We can’t expect to make headway if we simply wait until the signs of breaking points appear. And we must do a far better job of addressing socio-cultural forces that lead so many down a dark path.

Today, I can still see Mary and Mike sitting across from Kevin and me, hands folded in their laps, subdued in their adaptive state of tranquil obliviousness. What I remember most were their vacant, emotionless eyes, no longer capable of seeing mine that fought back tears as I listened to their stories of anguish. I was in my early 20s. This was scary and disturbing. I didn’t want to accept that they had become shells of former selves that their younger versions would find unrecognizable. I couldn’t grasp their isolation.

We may justifiably lament Mary’s and Mike’s fate. But if we don’t devote more of our energies and resources to improve our understanding of why so many experience desolation and address it pre-emptively, before it puts a chokehold on those most vulnerable, we will continue to fail them. And I would hate to think that years from now, some intern somewhere will be interviewing Jen, while forcing back tears over what her life might have been had she not fallen into an abyss.