A Hearty Appetite for Life

Peter didn’t sip, he gulped. He didn’t eat, he devoured. Our long-time biking group would routinely stop for breakfast on our Saturday and Sunday rides. Peter would scan the menu, his radar-like detection zeroing in on selections called The Belly Buster or The Hungry Man Special. Turning to the waiter, he’d request with a smile, “Please make sure the home fries are well done and bring extra butter for the toast.”

Peter’s appetite was part of his charm. And it wasn’t confined to food. He craved acquiring things, lots of things – shoes, clothes, bike accessories. He had quite the collection of fountain pens. Peter was lovable, the proverbial teddy bear, and the first to make himself the butt of the joke.

Unfortunately, Peter experienced an unrelenting barrage of health challenges in the past few years – multiple knee surgeries, each an effort to repair what went wrong in the previous surgery, prostate cancer, cardiac issues. The cumulative impact was taking a toll, at first chipping away at what had been his oversized zest for life and then completely eviscerating it. And yet, his recent passing caught us off guard. It felt sudden and unexpected, numbing.

About 40 family members and friends gathered on the cemetery road as Peter’s plain pine coffin was moved from the hearse to his final resting spot just a few feet in from the road. Huddled with my close friends, the biking buddies, I found myself staring at the pine box, its simplicity an ironic contrast to its inhabitant for whom the term understated was about as inapt as any descriptor could be. As the coffin was lowered into the gaping hole, his loss felt more surreal than sad.

It is now a couple of weeks after, and a weighty mournfulness has been kicking in. The tears shed by his two children and their families at the funeral were a powerful reminder of just how wonderful a father and grandfather Peter was. He would always speak with glowing pride about his son’s and daughter’s families, delighting in sharing photos of the most recent birthday parties and chortling about how his twin granddaughters had night and day interests. He adored them all, relishing the playful nicknames they had for him, like Papa Bear.

Since the funeral, I have been thinking about what it was about Peter that touched us so. I keep coming back to the notion of appetites, largely because Peter’s was huge and unrestrained. It was the first thing you noticed about him. It was impossible not to. He loved good cigars, good Scotch, and food, for which being good wasn’t a necessary condition, just that it existed and was within reach.

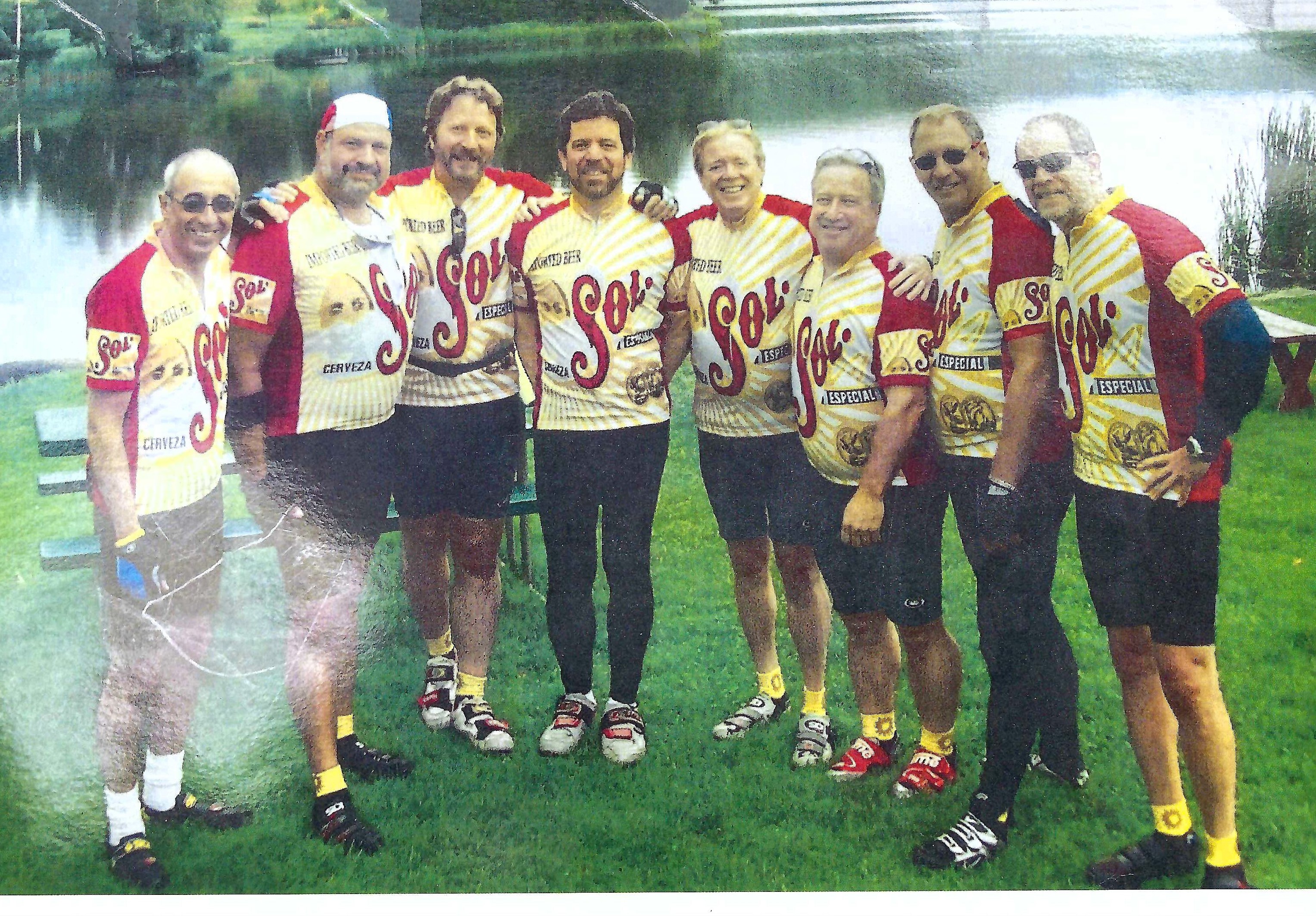

Each summer, for more than 20 years, our group has taken a four-day bike trip. We’d select a destination within a five-hour car drive from our New Jersey community, arrange for a place to stay, generally a Bed & Breakfast, and map out bike routes. We’ve gone to wonderful places for biking, like Vermont, Saratoga Springs, Newport, RI, the outskirts of Washington, DC, Shelter Island, and many others. By the time we would arrive at the B&B, Peter would have already researched the best ice cream places in town. It would not be uncommon for this self-sacrificial hero to make an excursion before unpacking to test them out and select the best for our group. What a guy!

Twice we went to the Amish region in Lancaster, PA. We’d take in the breathtaking serenity of the lush Amish farmland as we bicycled past horse-drawn buggies that reflected a bygone era. The inn we stayed at was managed by a Mennonite family, and on one of our trips they arranged for us to dine in the home of a nearby Amish family. Upon arriving at the home, we were struck by the elaborate network of electrical wires strung across the ceiling and connected to generators just outside. The family explained that the Amish’ resistance to electricity is a misconception. They are not opposed to electricity, but rather simply do not want to be connected to a grid operated by the state as that would be at odds with their commitment to self-sufficiency.

The evening at the Amish family’s home was heaven for Peter. First, of course, he struck gold with the sheer abundance of savory food graciously provided by the family. It was a bounty, an embarrassment of gastronomical riches. Peter was not shy about his appetite. Instead, he reveled in it, wolfing healthy portions (well, perhaps unhealthy would be more accurate) of roasted chicken and the creamiest mashed potatoes ever, freshly baked bread emitting the most enticing aroma accompanied by homemade apple butter with the perfect blend of cinnamon and sweetness, scrumptious meatloaf, mouthwatering buttered noodles, and an ensemble of traditional Amish desserts ranging from Shoofly pie to Whoopie pies, cake-like chocolate cookies richly filled with a thick cream.

But the more fascinating aspect of Peter’s appetite that evening was not related to food, but his intellectual curiosity. Quite simply, Peter loved learning, and our time with the Amish family was like a crash course in a way of life we knew less about than we thought. Peter peppered the family with questions about their lives, their relationship to the “outside” world, and their farming practices. The family was splendidly hospitable and eager to share, proving to be easy conversationalists. We did something with them we assumed improbable – we laughed together! And Peter was fueling the warmth along with all of us.

The family gave us a tour of the farm and took us into the barn where the cows were milked. The cows looked so contented, happy for the attention. We were shown how the milking tubes that attach to the udders work. Peter was like a sponge, taking it all in with gusto. Predictably, Peter couldn’t help but lapse into good natured goofiness. He sought to refine his “moo” so that he could converse with a particular cow that he took a shine to. Silly? Certainly. But hysterically funny. Even the cows seemed amused.

Peter’s curiosity was his strong suit. If he got hooked on something, he studied it from all angles. His greatest area of interest was the Civil War. Peter knew what transpired during each of the battles and who the major players were. He knew their backgrounds, where they received their training, how they died, and how their legacies unfolded over the years. He had even participated in Civil War reenactments and worked on teams to preserve the headstones of fallen soldiers.

He loved entertaining anyone within earshot with stories of the Civil War, adding humor to lighten the topic. He took special joy in enunciating the name of a well-known Southern general, P.T.G. Beauregard, dragging it out slowly with a southern drawl.

But more broadly, Peter had amassed a deep understanding of the social, political, and economic foundations of the war and how those underlying forces have continued to shape our nation’s character.

At Peter’s suggestion, we went to Gettysburg twice for our summer excursion. One year, we arranged for a park ranger to give us a bike tour through the battlefield. The ranger, delightfully gregarious and an expert on the Civil War, met his match in Peter in terms of knowledge of the war. It was fascinating to listen to their parries on points of controversy. For example, until very recently, there had been uncertainty as to the exact spot Lincoln stood when he delivered the Gettysburg address. Peter and the ranger unleashed torrents of scholarly corroboration to justify their differing positions on whether it was on one side or the other of a fence that was constructed following the war. We may dismiss this idea of the precise location as a triviality relative to the momentousness of Lincoln’s address. But for historians, each moment of that day is consequential on its own terms, and students of that decisive period in our nation’s history justifiably want to ensure that each moment is correctly recorded.

When I reflect upon Peter’s attention to that kind of detail and juxtapose it against the seeming lack of discipline when it came to his appetite, I realize that Peter could surely be thought of as a study in contradictions. I suppose like most of us, there were pieces of Peter that didn’t easily line up with others. He could talk ceaselessly, telling a story as though it was occurring in real time. But he was a good listener too, attending to our stories with equal intensity, effortlessly recalling a small detail mentioned casually a year earlier.

Peter was a personal injury lawyer, and I suspect his skills at listening and storytelling enabled him to serve his clients well. But he was well-suited for this profession for reasons beyond that. Despite his large size and bearish appearance – he could easily have been a mountain man with just a little cosmetic tweaking -- he had a tender heart and a special feeling for the underdog.

Peter’s death has made me think about the relationship between appetite and self-restraint, that perhaps they are two sides of the same coin. Self-restraint prevents an oversized appetite from propelling adventurousness into recklessness. And given the super-sized nature of his appetite, it was difficult not to think of him as reckless from time to time. We would even witness some cringe-inducing carelessness in his riding, like in his recent injured period when, from time to time, he seemed unable to dismount as quickly as would be required if we had to stop short.

But now, in the immediate aftermath of his passing, the relationship between adventurousness and recklessness seems to me more complex than clear. In fact, Peter might have exercised far more restraint than was evident. In this, I suspect something more fundamental may have been at play with his choice of legal specialty. Protecting someone who has been harmed from recklessness while seeking retributive justice from the offending party seems fitting for someone who himself hinted at having had a troubling and confusing childhood. His form of self-restraint involved converting his anguish into a noble professional pursuit.

Yet, this was difficult to see during all our years together. Maybe it was all the noise. Maybe Peter desired it that way. His live wire boisterousness may have trumpeted “look at me,” but it may also have had a deflective purpose, obscuring areas preferred hidden. As much as a spotlight illuminates, and Peter was skillful at shining it directly on himself, the shadow it casts is even larger. The paradox of attention is that it both attracts and conceals. As much as I thought I knew him, I wonder if I really did at all.

As he neared the end, Peter spoke of losing the will to fight on. What’s the point? he asked. He had had a good run, he said. He lamented the drip, drip, dripping away of his independence and mobility. Without that autonomy, he seemed defeated, deflated. While many can remake themselves based on shifts in their capabilities, Peter may not have been among them. It may be that his appetite failed him when it came to reinvention.

There is so much about Peter I’ll miss, so much we all will miss. His exuberance, his laughter, his wry smile, his saga-like storytelling. And of course, I’ll miss that appetite. I’ll always think of his appetite as his defining feature. He loved soaking in the world around him, relishing the moment without restriction. And underlying that consumption was a person of great decency. Much complexity as well, but great decency for sure.

I think what I’ll most remember about Peter is how he brought life to our group of biking friends. When I envision his self-directed spotlight today, the shadow recedes, and I see more vividly the unadulterated pleasure his appetite afforded, because at heart, sharing it was his greatest joy.