A Life of Giving

“I never met anyone like her,” Fischel declared with a conviction at odds with his softness of manner. It was 1979 and I was sitting with Fischel in the living room in his modest home in a Philadelphia suburb. He was about 90 and revealed just a hint of frailty, like a slight hesitation in his movement as though he had a recent fall and was being extra careful. But when he reminisced about her, his eyes lit up and a sweet smile swept across his furrowed face.

He was 14 and she was 13 when they met, he told me, confessing that he was so enamored, so deeply infatuated, that he became tongue tied. She was spirited, infectiously buoyant, he explained. But more, at such a young age she’d already earned a reputation for being a wise soul. Fischel said that even adults sought her advice on everything from child rearing to starting a business.

Fischel conceded that he could have only dreamed of a “courtship” with her, as it would have taken a miracle for her to return his feelings of affection. But deep down, he resigned that he didn’t have a prayer of measuring up. Besides, in those days, the early 1900s, most marriages in Jewish enclaves like Krasnystaw, a city in eastern Poland, were arranged.

“Chaya was special,” he concluded with a momentary faraway look in his eyes.

Chaya, the object of Fischel’s adoration, was my grandmother, whom I knew as my Grandma Ida, her Americanized name.

Ida was my father’s mother, and when I moved to Philadelphia for graduate school, my father suggested that I visit Fischel. The two had never met and my father knew of him only through stories his mother had shared about her childhood friends in Poland.

My father was pretty sure that Fischel lived in Philadelphia, so we looked him up and were surprised and excited to discover that his home was quite close to where I was living. How fortuitous! My father thought it would be fascinating for me to hear about my grandmother from someone who knew her when she was very young.

Fischel was an accomplished scholar, and it was a joy to hear him speak of his life and interests in addition to his stories about my grandmother. He had been a professor of foreign languages at Temple University, the school I was attending. In fact, even in his 90s he was still teaching, although on a very limited basis.

Certainly, though, he was most animated when he spoke of my grandmother. He delighted in sharing how so many in Krasnystaw seemed to know Chaya. A collection of boys could always be found hovering around her, he told me, and that each dreamed that her seeming unattainability applied only to the others.

The townspeople spoke glowingly of her, awestruck by her gift of an intellect beyond her years. She appeared to know how the world worked far from the familiar confines of Krasnystaw, even the gravity of warning signs for Jews in Eastern Europe that others downplayed.

But she also understood people and cared about them. Fischel gushingly offered that she was never short on time or patience to help others handle a day-to-day snag, like a disagreement over which market had the freshest food, or a major life event like the loss of a parent. She could console and advise, he observed, soothing hearts while offering a constructive path forward, finding that delicate balance between comforting and encouraging.

“She was never intimidated. Nor was she overconfident,” Fischel remarked. “Mostly, though, she was kind. And she never expected anything in return."

Leaning forward in his heavily cushioned gray armchair, as if to emphasize the point, he continued, “I remember when one of our friends, Hannah, lost her father. It was sudden, and Hannah was terribly distraught. Your grandmother spent two days making bread and soup for the family. When she brought it to Hannah’s house, she assured Hannah that she had lots of help, but I know she did it all by herself. It was as though she didn’t want to be thanked.”

Fischel filled in a gap in my understanding of my grandmother. She died when I was 13. Until then, I saw her often, so I had a good opportunity to get to know her. But it was as a child. How I wish I could have known her as I grew into adulthood. So much I could have learned from her! When she and Fischel were friends, they were young teens, around the same age I was when she passed away. The person he described seemed eons beyond where I was at that age, beyond anyone I knew then.

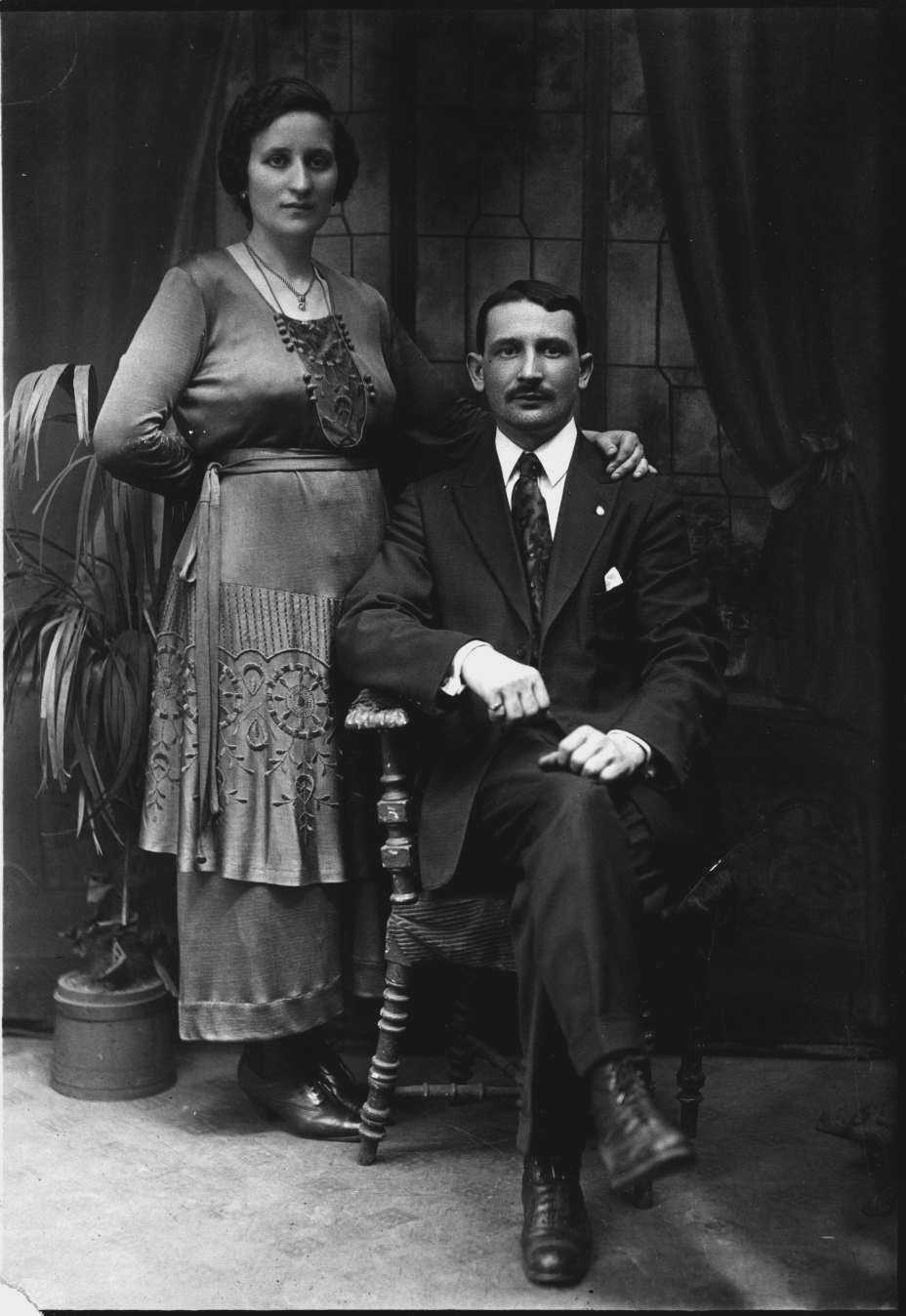

My grandmother’s marriage to Sam was arranged and they wed in Krasnystaw in 1908. Their first child was born in 1909 but, sadly, died about two

years later. They then had Doris in 1912, my aunt with whom I would become extremely close. A few years later, my Grandpa Sam left Poland to go to the United States in search of a life that would offer more opportunity for his family. He would send for them when he was established.

It took a while and finally, in 1919, my grandmother and Doris set out on a ten-day voyage to join my grandfather in the United States. Food in the starkly dreary confines of steerage was scarce, practically nonexistent. Until the very end of her life, at almost 107, Doris could still vividly recall the painful hunger she experienced during that trip. She often told the story of when a fellow passenger had given my grandmother two small sucking candies to supplement the daily diet of watery soup. She saved the candies to give to Doris on days when the hunger was almost too much to bear.

One hundred years later, Doris could still describe in detail what it was like to put the candy in her mouth. Though her senses were dulled from hunger, she remembered the sweetness, how she savored each second until its very last speck melted into nothingness.

Each moment of that trip was seared into Doris’ memory. But the most important recollection was how safe my grandmother made her feel. Despite the hunger and discomfort of filthy quarters, not to mention apprehensiveness about the uncertainties they would face in a new country, she believed she could get through anything as long as her mother was by her side.

The family settled in Brighton Beach, a stretch along the southern Brooklyn shore adjacent to Coney Island and a haven for immigrants from eastern Europe, Ukraine, and Russia. English was rarely spoken in this community that was dominated with Polish, Yiddish, and Russian.

It was there that George, my father, was born in 1921. Four years later, his sister Mildred came along, and five years after, their brother Murray was born.

The failure to speak English in my grandparents’ early years in the U.S. could show up in sometimes comical ways. My dad’s birth certificate recorded April 25 as the date of his birth, the same as his mother’s. Many years later, she explained that his birthdate was actually April 15. Apparently, when he was born, she was asked to complete an information form for the birth certificate. With no translator available in the hospital, she had to do some guesswork about the terms on the form and mistakenly put her birthdate in the space marked for her newborn. This became a fun family story, and we did continue to celebrate his birthday on the 25th.

In 1964, my Grandma Ida fulfilled her lifelong aspiration of traveling to Israel. According to my dad, the trip to Israel was not just a dream for her, but more like a cause. Having lost so many relatives and friends during the Holocaust, including her beloved sister Irina and her family, a visit to the country was akin to a pilgrimage to honor their memory.

I was nine years old at the time of my grandmother’s trip. When she returned, our family gathered to welcome her home. We were all eager to hear about her experiences, but she seemed most excited to share the special gifts she had brought back for each of us. My parents were delighted with the elegantly carved wooden box made by an Israeli artisan. My sister loved her gift, a silver necklace with tassels hanging from an aqua Eilat stone. I remember she put it on that instant and wore it often.

Next it was my turn. Excitedly, I opened the crinkly tissue paper wrapping to reveal a child-sized baseball glove.

A baseball glove!

My grandmother was beaming as she gave it to me, knowing that I loved sports and was active in Little League. I anticipated a story about how it was exactly the kind a famous Israeli athlete used.

As I put the glove on, I could feel a little tag up in one of the fingers. I pulled it out and read it. It had the name of the manufacturer and the words, “Made in the U.S.A.”

“Thanks, Grandma,” I said, hugging her. I then teased that she could have bought it here and saved time shopping in Israel. We all laughed, she more than anyone.

Then she said that wasn’t my only gift, that in fact, the glove was something she thought I might like because I enjoyed playing baseball so much. She then presented me with a small plastic bag wrapped in newspaper.

“This is a bit of sand I collected in Israel,” she said. “It’s from Jerusalem, right near the temple where I prayed for all of us. Over time, it will come to mean more and more to you.” And it has, mainly because it reminds me of her.

But there’s a story of Grandma Ida that I cherish above all.

For many years, my grandmother practiced a ritual a few times a week. Waking at about 3:30am, she’d head into the kitchen where, for the next few hours, she would prepare meals. These were not intended for her family, though in retrospect I imagine they were quite similar to what she cooked for us when we visited. There would likely be kreplach, savory meat-filled dumplings steeped in chicken broth; kugel, a baked pudding of deliciously sweet noodles, apples, cinnamon, and raisins; and tzimmes, a mouthwatering stew brimming with yams, carrots, prunes, and apricots.

She then lovingly apportioned these dishes into several meal-size containers before washing, drying, and stowing the cookware.

After packing the containers into three or four shopping bags, she would quietly slip out the door, careful not to wake my grandfather. He still had a remaining hour or so to sleep before heading out to his 12-hour shift as a laborer in a textile manufacturer.

My grandmother would then traverse the neighborhood, distributing the meals to families she knew were in need, telling no one that she did this. She deposited the food outside the doors of the fortunate recipients who would generally not know where the food came from.

At some point my grandfather and her children figured out what she had been up to, although if questioned, she tossed off a quick comment about just “running a few errands” before changing the subject.

One day in August 1967, as on many mornings, she awoke before dawn and prepared her meals. But this was not an ordinary morning.

Before she left to deliver the meals, she placed a note on the bedroom dresser for my grandfather saying that she was going to the hospital. My grandmother knew the cancer she had been battling was taking its final toll, and after what became her final round of food distribution for the needy, she checked herself in at the local hospital.

Two days later, it was there that Chaya, my Grandma Ida, passed away.

Maimonides, the renowned thirteenth-century rabbi and physician, spoke of eight levels of charitable giving. In the highest levels, the donor and recipient do not know one another. In such a circumstance, it is not possible for the giver to receive credit. And the recipient cannot be indebted to a person they do not know. The giver’s anonymity and humility convey to the recipient that they owe nothing. The recipient, free of obligation, can instead reflect exclusively on the act of kindness, a step toward actualization while extending help to someone else in need just as it was to them.

My grandmother had come from a community in which religion was central to a way of life, right out of a Shalom Aleichem story, like Tevye’s Anatevka. And even though she carried on the religious traditions, my sense is that adherence to rote religious practice was superseded by a moral piety grounded in respect for others, an abiding faith in the golden rule.

Once, when I was complaining about another kid – I can’t recall the issue – she said, “You don’t learn by condemning, you learn by listening. Don’t judge until you’ve done that.” I am forever grateful that it was a value my dad had taken to heart.

But as wise as my grandmother was, she was just as loving and fun. I remember her easy laugh and her warmth. Immensely approachable, she was our cheerleader, always gleefully proud of each of us and at her happiest when she was with family.

Today, as I reflect on her life, one lived with immeasurable decency, I marvel at just how inspirational a person she was. From that time at just 13 when she deflected credit for preparing food for Hannah’s family during their time of mourning, until her final meal distribution in her dying days, she embodied a saintly generosity. She sought not only to ease others’ hunger, but through her selflessness she nourished their dignity as well.

In Hebrew, “Chaya” means life, and her life was a model of righteousness, humility, and virtue. Fischel was moved by the grace in her soul even at their early age. And since that time, over the course of her extraordinary life, many had been given comfort by her, most never even knowing her name. It is humbling to think about such a legacy, and I am so proud to be her grandchild.