Gaming the System

Cal and Sophie were preparing to bake a red velvet cake for a friend’s birthday. Cal stared at the canister containing the bag of flour on the top shelf of the pantry, taking a moment to judge if he needed a stepstool to reach it. He opted to stand on his tiptoes. As his outstretched fingers glanced the canister, he felt a twinge in his left knee. It didn’t hurt – it was more like an unwelcome surprise – and it left just as quickly as it came.

A week later, as Cal was getting out of the car to drop clothes at the cleaners, the same pinch occurred. But this time, instead of a minor twinge, it felt like a sharp stab deep in his knee that lasted about five seconds before subsiding.

Over the next few months, the sensation came upon him more frequently, mostly when he walked on uneven terrain or pivoted too quickly when shifting directions. A couple of Advil generally did the trick, easing both the ache in his knee and his anxiety that the problem was more than simple arthritis.

Unfortunately, that didn’t prove to be the case. Fast forward two years and Cal was scheduling knee replacement surgery.

This story is not so much about his surgery as it is about the sheer frustration that Cal – like so many of us – experienced with health insurance.

Surgery went well. In fact, it went so well that Cal’s surgeon thought he could take some steps later that afternoon, with crutches of course. Physical Therapy (PT) began the day after surgery. Cal’s surgeon prescribed 6 weeks of PT, 3 times a week. For the first week, a therapist came to the house.

Cal’s progress was promising. After just a couple of days, he even discarded the crutches, though the therapist encouraged him to use them when he felt fatigued.

On his first outing to PT a week after surgery, Cal was greeted by Dwayne, the intake coordinator, who asked him to complete some paperwork, which included questions about pain.

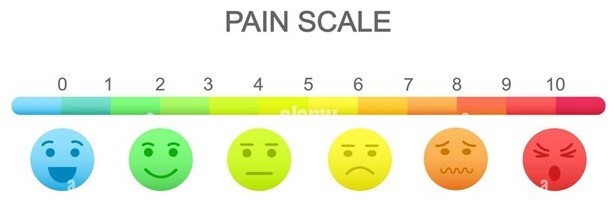

To make it easy for patients to rate their discomfort, they are often presented with a graphic consisting of six facial expressions ranging from pain-free on the left to pain-ridden on the right.

Cal wasn’t sure which number to circle. He had been free of pain, except for mild discomfort when he woke up and got out of bed. He considered circling 0 since he couldn’t really call what he felt pain. But it occurred to him if he circled 0, maybe the therapists would think he didn’t even need the therapy, and he was sure their supervision of his exercises would be important to his full recovery.

After mulling it over for a minute or two, he concluded that this amount of thinking was overkill, and he quickly circled 1.

Next, Cal was evaluated by Allison, the physical therapist with whom he would work for the duration of his visits. She was pleased with his flexibility and range of motion and was confident that his recovery would be complete and swift, provided of course that he stayed true to the therapy program.

In the meantime, Dwayne submitted the paperwork to Cal’s insurance company, I’ll call TFU.

Little did Cal know, but circling 1 triggered behind-the-scenes activity at TFU that would determine the fate of his physical therapy program, and by extension, his recovery.

TFU is a very large health insurance company. They employ dozens of people whose jobs are to review claims and investigate denials that are challenged by patients or their doctors.

Can you guess how many people are employed in these jobs in the United States?

An astonishing 300,000! With salary and benefits of about $100,000, that comes to about $30 billion per year solely for claims assessment staff.

But that doesn’t tell the whole story. Not even close! When we add in all the supervisors, office space, information technology, and the legal costs for claims that go through adjudication, the overall expense on claims management is closer to $100 billion!

Just think about it. That $100 billion isn’t spent on taking care of people – it’s spent just on claims deliberation!

But that’s not all, and not even the worst of it. When claims are denied, people who need care often delay seeking it or give up on getting it at all. What happens next is no mystery. Many get sicker, paying a price with their health and more expensive follow-up treatment.

Bill was half-way into his second year of retirement from his practice as an orthopedic surgeon when he found himself growing bored. He took a part time job reviewing claims at TFU. On his second week, Jason, a claims department supervisor, asked to meet with him.

After some light chitchat, Jason got to subject at hand: “Bill, of the 136 claims you reviewed since you started, 133 were approved.”

“Yeah, I know. Most seemed routine.”

Jason, who struck Bill as a young go-getter, started off with a flattery offensive. “Sure, most claims are routine. And who better than a surgeon with your experience would know that. That’s why we’re grateful to have you on board.”

Bill knew full well that being buttered up was a seductive precursor to what was coming. “Happy to be here, Jason. But it looks like you have something on your mind.”

“I’ve been in the claims field for eight years now. I may not have seen it all, but I’ve seen a lot. Doctors ordering too many tests to cover their ass. Fraud. Crazy stuff. Last week, a claim was passed up to me for treatment for a rare form of cancer. Forty thousand dollars a month that would keep the patient alive for 6 months max. We fought it on grounds that it was experimental.” Proudly, he added, “And we won that one!”

Bill was taken aback. “It’s tough for me to think of this as winning and losing. My career has been dedicated to taking care of people, not judging the price of life-extending treatment.”

“Well, here’s the thing,” Jason declared, his faux charm morphing into insolence. “The standard in this business is that roughly 20% of claims should not be approved outright. So, our policy, not that it’s written anywhere, is that we follow that industry standard. You are new to this, so of course we are not concerned about your denial rate, at least not yet. But so far your denial rate is around 2%, almost 18% lower than the average.”

“Are you suggesting that I keep a quota in mind instead of evaluating each claim on its own merits?”

“Of course not. But here’s a little secret. I get to keep my job, and hopefully move up in the company, based on my department’s success in denying or reducing claims. And by success, I mean they don’t get overturned on appeal. That’s the financial model that keeps us in business, and this company has a better track record than most.”

“I see. But I don’t think I can work that way,” Bill retorted. “I have to judge each claim based on medical necessity.”

“Then we agree. But it’s how we interpret the word necessity that makes all the difference. Let’s take a look at this one claim that you approved,” Jason said as retrieved a claim summary from a folder on his desk.

“Knee replacement. Surgeon orders 18 PT visits. On 4th visit, the first in-office, patient reports virtually no pain. The therapist indicates mobility and balance without crutches are good, consistent with progress at 5 weeks.”

“Yes, I remember that case. PT for 6 weeks, 3 times a week. That’s reasonable for anyone with that type of surgery,” Bill interjected.

“But with his progress, we can drop it to 10 visits, tops. That’s what the guidelines stipulate. Even 10 visits would be generous.”

“He may have only a little pain and he is ambulating well, but the healing is far from complete. Premature withdrawal from PT could create complications,” Bill explained.

“Let’s cut to the chase,” Jason said, his tone now tinged with impatience. “There’s no way I could authorize this. Even if I agreed with you, my bosses would have little tolerance if I approved a case like this. This is how the system works. As it stands now, my department has a 19% denial rate for claims. If I don’t get that up to about 22%, I’ll have no chance at a promotion.”

“I’m sorry you feel this kind of pressure,” Bill responded, guided by his conscience. “I get that you have be on the lookout for fraud and abuse. But that’s different from depriving people of the care they need. This doesn’t work for me, so it’s probably best that we part ways.”

The insurance claim was handed off to another reviewer who carried out Jason’s decision to limit reimbursement for Cal’s physical therapy to 10 sessions, 8 fewer than what his surgeon prescribed. A letter stating this decision was simultaneously mailed to Cal and to the PT office. By the time the letter arrived, Cal already had completed eight sessions, with only two remaining.

Cal was understandably upset. He knew he was making good progress, but he worried that he might do the exercises incorrectly if he was on his own, potentially causing damage or interfering with progress.

Allison asked Cal’s surgeon to appeal TFU’s decision. He agreed to do so, but said it wasn’t uncommon for insurance companies to pay for fewer treatments than the prescribed number. He said that this was the most aggravating aspect of dealing with insurance companies.

A week later, the response to the appeal arrived in Cal’s mailbox. It contained a single sentence: “The extension request is denied due to lack of reasonable medical necessity.”

“This is crazy,” Cal shouted to Sophie, who was in the next room. “Can you believe this. I got kicked off physical therapy because I’m doing well! It’s outrageous.”

A few days later, as Cal was winding down his final PT session, Dwayne asked if he would like to continue at his own expense. Cal asked what that would cost.

“$162 per session,” Dwayne responded.

“Maybe. Let me think about it,” Cal offered, though he expected to forgo because he was feeling so well and couldn’t justify the expense

A week later, Cal decided to add some deep squats to his exercise routine, assuming they would help him regain a full range of motion more quickly. After all, he figured, he was making splendid progress and was eager to get back to tennis.

The first couple of days went well. On the third day, he experienced some tenderness in his knee. It was relatively mild, so he thought he’d work through it by continuing the squats. When he awoke the next morning, his knee was swollen and discolored, a multicolored mosaic of purple, red, and blue. As he got out of bed and put his foot on the floor to stand, he felt some serious pain and fell back into bed.

“You overdid it,” his surgeon reported while examining Cal in his office. “Why didn’t you follow the PT exercises, no more, no less?”

“I felt good, like I could handle it, and I thought it would help my recovery.”

“You tore tissue from doing more than you should. I’m ordering PT. This is considered a re-injury, and because of that, the insurance company will not be able to turn you down this time.”

Would Cal have re-injured himself if his PT had not been denied? We may never know, but since he was diligent about following Allison’s directives, it’s a safe bet that the injury would not have occurred had Cal been under her watchful eye.

The irony in all this is that TFU wound up paying more than twice what it would have had it not denied Cal’s claim.

As Cal limped out of his surgeon’s office, clumsily negotiating the doorway on the very crutches he thought he’d never need again, he considered two lessons he’d learned from this ordeal, lessons learned the hard way.

One is that he should have been more careful, and certainly should not have taken it upon himself to aggressively add to the exercise program without at least calling Allison to check if it was okay.

But he also learned that honesty may not be the best policy when it comes to health insurance. He resolved that when he fills out the pain scale next time, he’ll be more conscious about selecting a pain level that would mitigate the likelihood of TFU cutting off his therapy.

So here we are, forced to game the system to make it work for us. Jason must deny claims to keep his job. Cal must report more pain to keep his benefits. Allison must challenge the denial to keep her patient healthy.

On a national scale, that very tug-of-war costs us $100 billion a year, not a penny of which goes toward helping people get well. Surely, we should be able to do better.