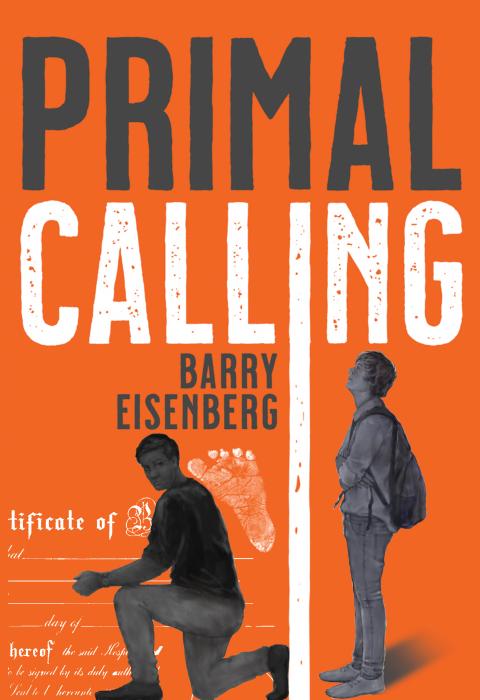

A One of One

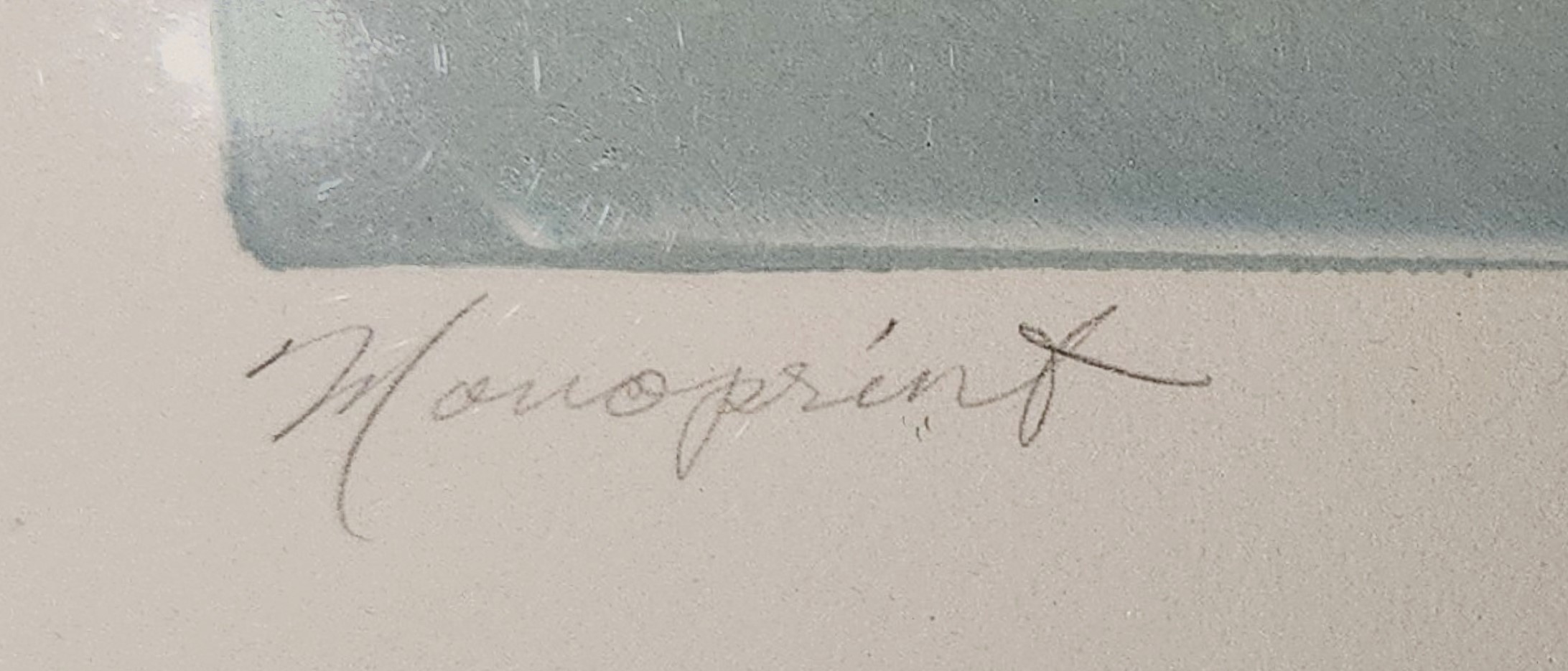

“That painting. It’s intriguing. Do you know the artist?” I asked, gesturing to the multicolored swirl that seemed to flutter off the canvas. It was as though a pastel-streaked linen surrendered to a gust of wind. I took a closer look. The title, aptly Crimson Wave, and the artist’s signature were scripted faintly in pencil in the lower margin.

“Oh, yes, of course, Michael. He’s up and coming,” Emmeline, the gallery owner, replied, offputtingly tossing out his first name as though we recently toasted his latest gallery opening over Eggs Florentine at a Hamptons brunch.

What if her “Michael” was not a byproduct of pretentiousness or a sales ploy, but that his name was genuinely worthy of dropping. Lest I reveal my cultural depravity, I went along and asked if she had been showing Michael in her gallery for a long time.

“It’s been a couple of years since I discovered him.”

Discovered him. Is she taking credit for his success, which, by the way, had yet to be confirmed, or did she mean she learned of him?

Ah, the words we choose.

“It’s good to know you connected with him on his way up,” I offered, a benign remark that granted Emmeline a smidgen of validation without any real substance.

“We’re fortunate to have some of his work. Lots of interesting experiments with color and dimensionality. Such a fascinating palette. Hues not often intermingled so daringly.”

The vocabulary of this exchange was rapidly shifting her way. I could only imagine that each time I nodded, the price for her Michael went up $100.

This story is about words, one in particular. No, it’s not discovered or learned, though despite their meaty Venn overlap, the gulf between them can be massive. Rather, it was a word that appeared on the lower left corner of the canvas, a simple word that I found terribly confusing.

“What does the word monoprint mean, that word right there,” I asked, pointing to the term that would prove increasingly elusive to definition the more I struggled to find it.

“Well, with a limited run, you know how many reproductions were made and what number in the series each one is. If you see 18/175, you know that this would be the 18th reproduction in a series of 175 in total. With this piece by Michael, well, it’s different because it is the only one in the series. It’s a one of one.”

“A one of one,” I repeated, trying to grasp the concept. “Wouldn’t that make it an original since there is no other.”

“Sure,” she replied.

But there was something about Emmeline’s look, a hint of impishness in her smile. It came and went so quickly that I could have been mistaken. But I couldn’t shake that shred of uneasiness that maybe what she said didn’t match what she thought. I wanted to feel confident that this was not a reproduction, but rather an authentic work of art. But there was that look. Was it sly or was it innocent? Were I to take home the Michael would depend in how I sorted that out.

Noticing my hesitation, she doubled down, “Sure, it is certainly the original reproduction.” Then adding, after a beat, “If it will help for you to think of it that way.”

What??? Now there’s an oxymoron if ever I heard one. Civil War. Old News. Silent Scream. Open Secret. And to the list we can now add Original Reproduction.

“Well, what other way is there to think of it?” I asked, my confusion/clarity ratio shifting weightily toward the former.

“Yes, because it’s a one of one you may think of it as an original.”

Each time she issues a declarative statement, she manages to squeeze in a qualifier, usually so tiny it’s hardly noticeable. But, oh, how unnerving!

“Aha. It’s that word may that’s puzzling. Can we say that it is an original?” I implored.

“Well, you wouldn’t be wrong.”

“But would I be right.”

“One wouldn’t fault you for believing you are right.”

“Would the one who wouldn’t fault me by any chance be the artist, you know, Michael?”

“Ah, Michael,” Emmeline gushed, a lilt returning to her voice. “Oh, I just know that Michael would not fault you at all.”

Was she drawing on a real familiarity with Michael or was she inventing it. I couldn’t help but think she’s good at this.

“Let’s try it this way,” I proposed. “The actual, real, bona fide Mona Lisa is hanging in the Louvre. That’s the one painted by DaVinci. He held the brush directly to that canvas. There are millions of reprints all over the world. Would you say that this work by Michael is like the original of the Mona Lisa or is it a reprint like those millions of others?”

“As much as I am impressed by Michael’s work, it would hardly qualify to be in the same discussion as the Mona Lisa.”

Nice dodge, Emmeline.Touché.

“No, no, that’s not how I meant it, and sorry if I wasn’t clear,” I said. “I am just trying to comprehend what makes a work of art an original or not an original.”

“And that’s exactly what I am trying to help you with. Since there are no other reproductions, this is the only one of its kind. And that’s why you can safely say it’s an original.”

“I get it, but it’s the difference between safely and accurately that I’m trying to get at.”

“Safely. Accurately. In this case there is no difference.”

“But it’s a difference in my mind, the difference between buying it or not.”

“That’s not how we should think about art.” Ooh, a deft move – Emmeline was shifting to an irrefutable chastening strategy. “The only question is whether it appeals to you and you want to look at it.”

“I like it and want to look at it. But buying it depends on whether it’s an original work of art or a copy.”

“Which I have now answered multiple times, including sharing what I am certain would be the artist’s impression.”

A sterner Emmeline was emerging. I couldn’t tell which may have been irking her more, my curiosity or my skepticism.

“Can you walk through the process of how this work of art came to be.”

“Sure,” she said with her well-cultivated cordiality, though I sensed she resented the need to dumb down to my rank pedestrianism. “The artist paints it on a block, which is then transferred to a silk screen and ultimately pressed onto the canvas.”

“Why wouldn’t he paint it directly onto a canvas?”

“Well, certainly the overall effect would not be same,” she asserted, as though stating the obvious. Then, sliding effortlessly into her comfort zone, and in her silkiest tone, “The swirls are more pronounced this way, bolder, seductively so, allowing you to drift right into the painting and become stirred by its mystery, immersed in it.”

“Hmmm,” I thought. I stepped back and looked at the painting again. Her words were beginning to resonate. She was actually articulating what I felt when looking at it. I began to see her in a different light. When describing the painting, her tone was more natural, and like the painting itself, it flowed breezily, freely, unencumbered. She sounded more, well, genuine.

But I was not ready to jump on her bandwagon just yet.

“Ok,” I granted. “But let’s say he didn’t stop with the monoprint, and instead made a second print. It would be a bi-print, if you will. Would they both be originals or would they both be reproductions?”

“The way the process works, that would be impossible. All the color is transferred, so only a monoprint is feasible, not a bi-print, a tri-print, or a deca-print,” she said, chortling at her inventiveness, which if I’m being honest was a rip off of my observation. But why would that matter in her world of mixed-up originals and copies.

Now wanting to convince myself beyond a reasonable doubt that it was an original, I leaned into her argument. “So, can I correctly assume a reproduction is impossible, and that only a single production can be done.”

“Exactly!”

“And that entire production, from the paint on the woodblock to the transfer onto a canvas, is part of a process in which reproductions are not possible, right?”

“Oh, Michael would be so pleased to know you understand his process,” she effused, gushing once again, which always seems to be triggered at the mere mention of Michael. I’m amazed at how many times a day Pavlov is proven right.

“Wonderful. I’m sold. Please wrap up Crimson Wave.”

I watched as she meticulously wrapped the painting. She carefully taped neatly cut strips of bubble wrap around the edges, then cushioned the frame with soft cardboard material. It took her about 15 minutes. It occurred to me that she must have packed thousands of paintings, and she approaches each as though swaddling an infant.

Emmeline had owned this gallery for 25 years. She was not conning me into buying a painting. As much as I may have taken her for a snob, she probably saw me as boorish, focused so predominantly on the painting as a commodity that I couldn’t enjoy it solely for its aesthetic appeal, for the sensations a work of art may evoke.

I came to realize that the words she used to describe the painting were not disingenuous, but a reflection of what she loved about her work. They may have sounded over-flowery to me, but the ethics of communication would dictate that we remain open to meanings others have for their words. This is a lot tougher than it sounds. Especially these days.

When I look at Crimson Wave today – and to be fair, it is a style that has fallen out of fashion over the years – I’m reminded of that. The billowiness suggests that our need for certainty is sometimes best left suspended, that we should never get so fixed in our assumptions that we lose sight that the positions of others also have merit.

As we completed the transaction on the day I bought the painting, Emmeline looked up as she put her final touches on the packaging, beaming as she offered reassurance: “Take it. Love it. I’m sure it will be happy in its new home. I know Michael would be thrilled.”

“So happy to know he would be pleased. Please be sure to let him know he has a new admirer. When do you think you will see him next?”

“Why, I see him every day. After all, I’m surrounded by his art. I’m a firm believer in the oneness of art and its creator.”

“Of course, of course. But I mean when do think you will see Michael next. Not his artwork. I mean see the real him, the real Michael.”

She looked up, and with a wink and her signature smile, chirped, “Well, when you say the real, do you mean—"