Letters from my brother

In preparing for our move to a new house next spring, Amy and I have been slowly cleaning out our basement. Poring through the mass of boxes we have not opened since we moved into this house many years ago, it’s been like stepping into a dusty time machine. Two weeks ago, during one of our clean-out sessions, I came upon an old black briefcase – its laminate exterior flaking off from age – tucked away between plastic bins filled with our kids’ baby blankets. I hadn’t opened that briefcase in decades. But I did know what was inside. Since I was sure it would evoke strong feelings of nostalgia, I thought it best to open it some other time, when I could look through without feeling rushed. But at that moment, I couldn’t help myself and vowed to indulge in nothing more than a quick glimpse. The rusty latches were difficult to pry open but as they did, the briefcase, swollen with memorabilia, practically exploded, the contents spilling out.

These were my keepsakes from the summer I spent in Israel when I was 13. The first thing I noticed was a plastic bag filled with a thick stack of letters from my family – my parents, my brother and sister, and my grandparents. I had forgotten how many letters there were, and my initial reaction was awe from the sheer number. “Just one” I told myself as I decided to peek before getting back to the task of sorting stuff in the basement. I plucked the top letter from fhe pile. It was from Larry, my brother.

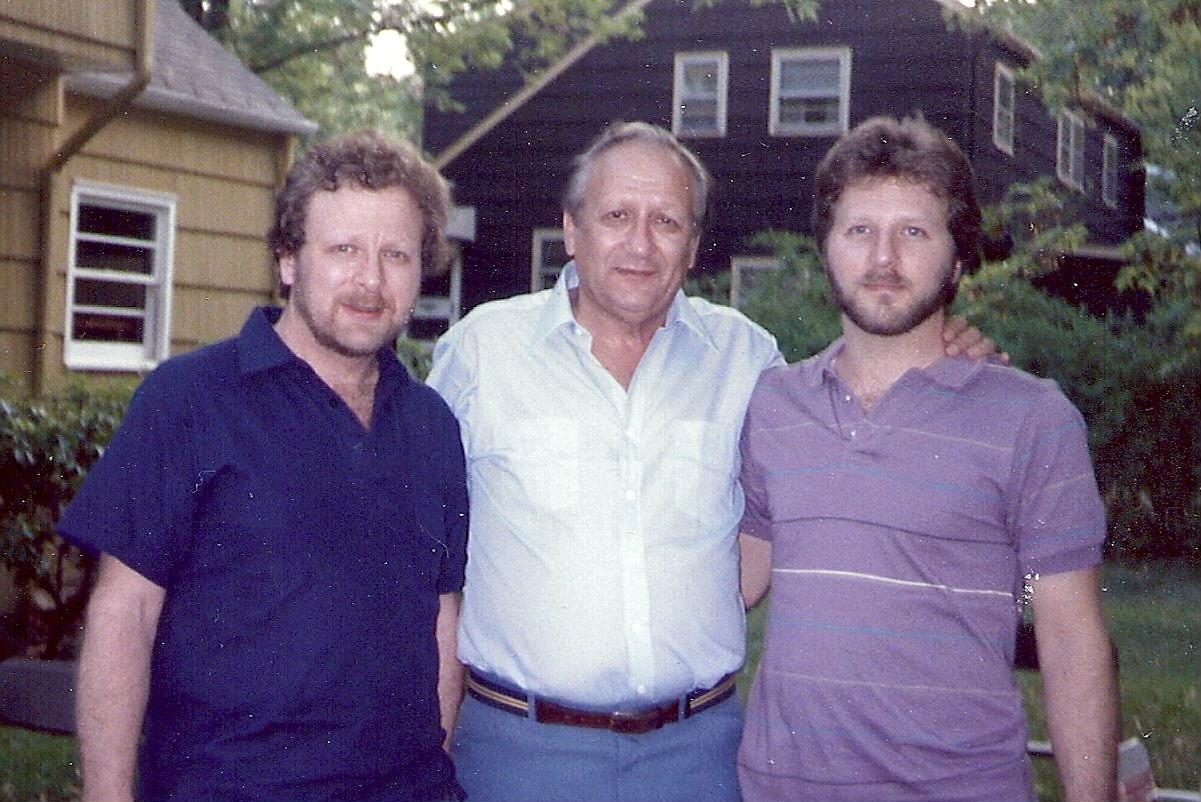

Staring at the letter and reading just the first few sentences were enough to choke me up. It was a stunning sensation, at once bringing into focus the magnificent relationship I had with my brother and what his loss has meant to me. Larry passed away ten years ago, following a two-year bout with an aggressive form of prostate cancer. As brave and as strong as he was, he was no match for that relentless foe.

Larry and I had always shared a very close relationship. He was seven and a half years older than I, and from as far back as I can remember he generously included me in his world, allowing me to tag along with his friends, even when I was as young as five. Undoubtedly, I was a pest – what younger brother wouldn’t be – but he always encouraged me to come along. His friends were also welcoming – Mike tried to teach me to whistle while Greg made it his mission to teach me how to snap my fingers. Their efforts produced limited success, but I loved the attention.

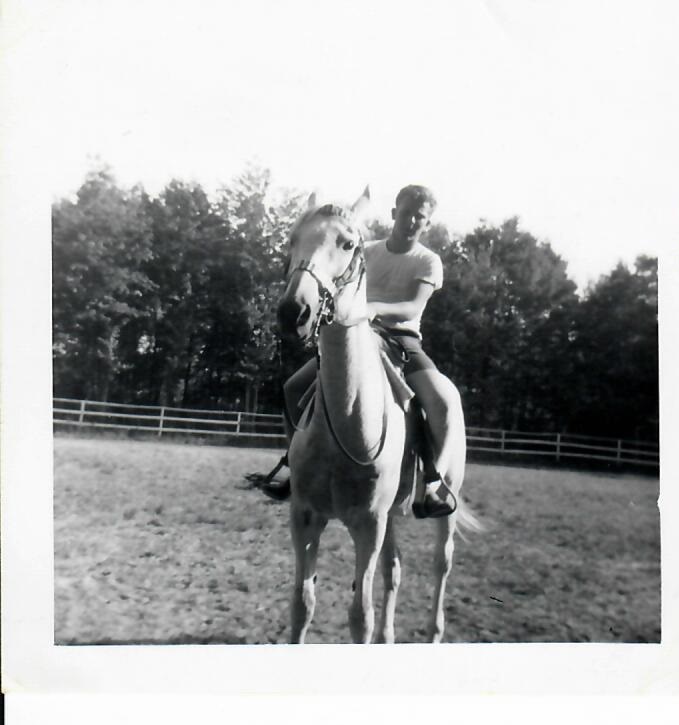

When Larry was sixteen, he got a job as the horseback riding counselor at a summer sleepaway camp. Of course, if Larry was going to be there, I would as well. (It has never been clear how he got that job as I don’t recall him ever riding a horse. But, in my mind, Larry could do anything!) A couple of weeks into the summer, Larry arranged for me to drive the six and seven-year-old campers around in a buggy pulled by a pony. This became my afternoon “job” and, at nine years old, I felt so special.

The pony was older and had a calm demeanor, so I guess the camp directors thought it was safe for me to handle this responsibility, especially under my brother’s watchful eye. But one day, something must have frightened the pony because all of a sudden, he quickened his pace and began to gallop down the dirt path that led to the horse trails. I was bouncing up and down like I was on a runaway train, practically falling out of the little wooden seat as I tightened my clutch on the reins. In retrospect, everyone should have been panicking, but it was the most exhilarating experience, and the little kids in the back were giggling with delight as though all this was intended. The fact that nothing terrible happened remains a mystery to me.

Another memory is the time that Larry got his first car. He must have been 17 or 18, and I was ten or eleven. He couldn’t wait to give me a ride and I couldn’t wait to be his first passenger. It was a Ford Fairlane convertible, and the coolest thing ever. A few years later, we took that car to our weekly basketball games with friends.

When he was a young man just starting out, Larry opened a small boutique seafood eatery in New York City, a venture that lasted but a couple of years. During my late teens, I worked at the restaurant, going in at dawn to prep for lunch before heading to Queens College for my afternoon classes. I’d spend a few hours cutting lemons, unfreezing shrimp, and shucking oysters. The other guys who worked there and I had contests to see who could shuck the fastest, which helped us get through the monotony of the repetitive tasks.

Except for that brief foray into the restaurant business, Larry’s life-long career involved importing and exporting precious stones. While I was in high school, he took me along on some weekend business trips. For years after, we laughed recounting one of the trips when he was just starting out. We were traveling through tiny towns en route to Ohio, stopping in jewelry shops along the way to either make a sale or, at the very least, a connection for future business. With funds being what they were back then, the goal was to stay in the cheapest motel possible. Finally finding one at about 1:00 AM in a small, sleepy town, and feeling very exhausted, we were grateful that we were about get some desperately needed rest. As soon as we settled in, we discovered the reason for its low price: neither the plumbing nor the heat worked. It must have been about 30 degrees in that room. But too tired to venture out to find a new place, we put on all the clothes we had and waited it out until morning, shivering through the night.

During my senior year of college, I lived with Larry and his young family. A room in his basement was my living quarters, and it was early in that Fall semester that Amy and I met. We had a great time cooking in the little kitchen area adjacent to my room. It was in that space that Amy taught me how to play the guitar, and I still have the guitar she bought me for my birthday soon after we met.

Throughout our adult years, Larry and his family and I with mine spent much time together despite living in different cities. He and I were always in touch, speaking by phone at least a few times a week. One of us would call the other, typically around mid-morning, just to catch up. Even if the call lasted a minute, that was enough. The term “touching base,” as trite as the phrase sounds, is exactly what our calls were for. Little did I realize at the time how precious the “base” we touched was.

So, about the letters in the briefcase…

My summer of 1967 was spent in Israel, where I attended a camp that took campers touring through the entire country. During that summer, I received seven letters from Larry, one letter each week. As I read them now for the first time in decades, two things stand out.

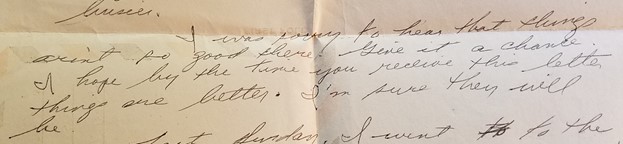

First, I am reminded of how caring and protective Larry was, my buggy-driving assignment notwithstanding. I remember feeling homesick for the first few days of my time in Israel and writing home about it. Within a few days, I received letters of reassurance from my parents, Larry, and my sister, Roberta (whom I’ll write about in another blog). Larry’s first letter to me had the sort of “chin up” encouragement that always made me feel better.

At the time, Larry was twenty years old, had just started dating his future (and wonderful) wife, had just started a job, and was surely preoccupied with all that a twenty-year-old could be preoccupied with. And yet my feelings had managed to penetrate. He began the letter this way:

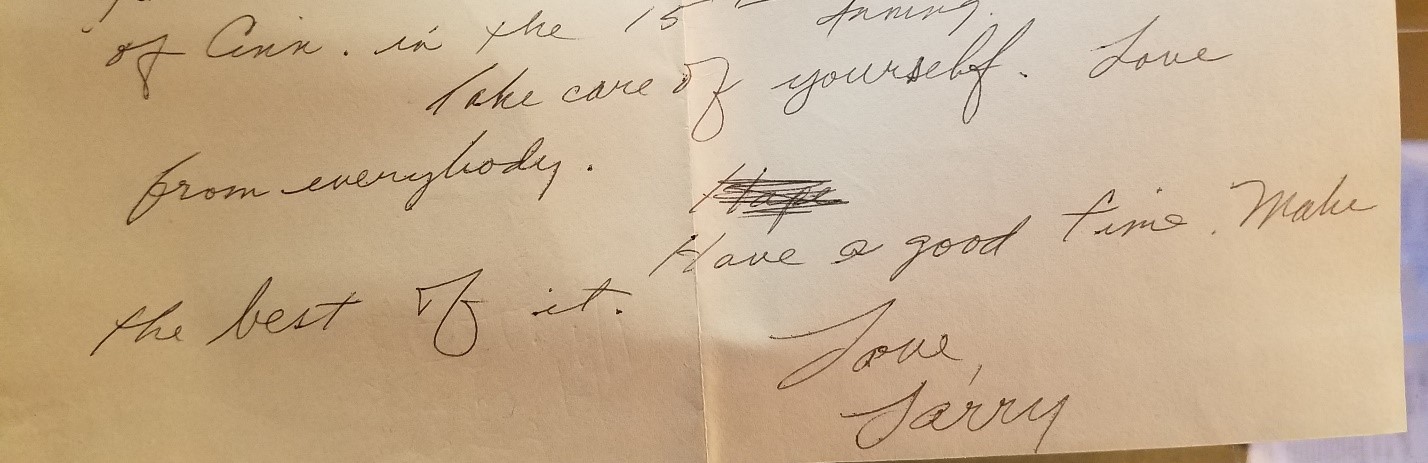

If Larry said things will get better, I knew they would. He ended that first letter this way:

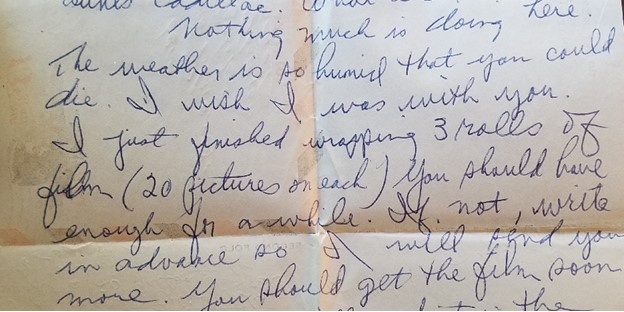

And his caring came through in little gestures, in all the little things people do for those closest in their lives. For example, I found myself taking more photos than I had anticipated, chronicling every moment. Larry took it upon himself to replenish my dwindling supply of film.

Nothing about Larry’s attentiveness and thoughtfulness surprised me. But I had forgotten exactly what it looked like, what forms it took on an everyday basis. Back then, I could take for granted that if I needed more film, it would be in the mail the next day.

The second thing that struck me as I read through the letters was being surprised by the topics he wrote about. Lots about baseball and politics. He routinely referenced a Mets win or a Yankees doubleheader, highlighting a player who did especially well. Judging by how much he wrote about it, sports must have been something he and I discussed often. But I didn’t realize until reading these letters how often and how detailed our discussions about sports must have been.

1967 was also the summer of riots in Newark, with racial tensions spilling over into violence. Larry mentioned the riots a few times in his letters, though dispassionately. In retrospect, it seems he was trying to gain some perspective on what could underlay and provoke such anger and bloodshed. I suppose we all did, as it seemed to signal that the cocooned world we inhabited rendered us oblivious to socio-economic conditions that disadvantaged so many in this country. It was a time in which assumptions were being upended as we were gaining insight into the pain and despair that comes from being treated as second-class citizens. But we lacked a language for it, struggling to home in on a vocabulary that acknowledged that even in our very modest way, what we had going for us was privilege. And there was something unfair about that.

In the couple of weeks since I read Larry’s letters, I have been struggling to understand why I would be so surprised by what he wrote. I have a hunch that if he was still alive, I wouldn’t have seen the content and themes of his writings as unusual. His passing was an abrupt end to a lifelong conversation, each moment contextualized by all those that preceded it and that were expected to follow. But in the years since his passing, the miniscule bits and pieces of our conversations have gotten a bit blurred in my memory.

While Larry was alive, our conversations were like the proverbial trees in a forest. In the past ten years, they have slowly become obscured by the forest. Make no mistake, the forest is wonderful. I treasure it. But what I wouldn’t give to enjoy the magnificence of a tree again, any one of them, in all its simplicity, and bask in the splendor of its mundanity.

Which is why the letters are so captivating, so special to me. I am very fortunate to have them. They tell a story of what Larry’s brotherly generosity actually looked like, how it was expressed in the tiny, everyday ways we show love to those in our innermost circle.

Reading the letters and revisiting moments of the bond my brother and I shared has been extraordinarily heartwarming. Larry’s letters will forever help me to appreciate that those things we so often take for granted come back to us as the most beautiful parts of our lives.