Remembering My Mother

In the late 1970s, I moved out of the apartment where I had lived with my parents for the previous 10 years. Amy and I had just returned from a month-long cross-country camping trip and were moving to Philadelphia together where I was to begin graduate school. At the same time, and finally empty nesters, my parents decided to leave Queens, NY as the sunshine and beaches of Florida beckoned. Soon after their move, during winter break, I flew down for a quick weekend visit. I took a late flight out of Philadelphia and arrived at around eleven p.m.

My parents, George and Sylvia, had bought a modest ranch style house in a suburb of Ft. Lauderdale. They were eager to show off their new home, which felt palatial in comparison to the small apartment in Queens. They were especially excited with the pool and screened-in patio, something they never dreamed they would have. Naturally, my mother offered food – a platter of tuna salad and bagels – but she was most eager for me to go for a swim and get started enjoying the warm January weather.

As we headed out back, she switched on the patio lights, which had the effect of a giant spotlight exploding in a sea of darkness. I felt incredibly conspicuous jumping into the pool, concerned that the splashing would shatter the stillness of the night and rouse the sleeping neighbors. But the pool looked so inviting and my mom’s face was beaming with anticipation, so I slid in as gently as possible, so pleased at my mom’s delight.

On my next visit, I arrived to find a plate of fruit and snacks waiting for me on the patio table. A familiar-looking towel was draped over the back of the patio chair; there was no question that there would be a midnight swim. This time, my parents joined me, along with my sister Roberta and my nephew Jamey, both of whom lived with my parents.

That midnight swim would become a ritual. Each time Amy and I would go to Florida for a visit, a midnight swim would be in order on the first night. The same green towel I used after showering as a kid in Queens was always draped over the chair, such a warmly nostalgic touch. As years passed, our family grew and the kids began participating in the ritual. Slowly, one by one, plush new towels replaced the faded ones. I missed that scruffy threadbare cloth that always reminded me of my youth. But one thing never changed – there would always be a platter of fruit and snacks, and yes, tuna salad and bagels.

The tradition of the midnight swim was one of my mother’s favorite stories to tell and will always be among my most treasured memories.

Today, January 29th, would have been my mom’s 100th birthday. Eight years ago, lung cancer claimed her life. Like most who have had the blessing of a parent who lived a long life, I have thousands of prized memories, but it’s the everyday, ordinary occurrences that ring loudest for me. Her gleeful smile as I jumped into the pool is indelibly etched in my mind. It was an unreserved smile, filled with joy, a blend of contentedness and exuberance. The simplicity of those moments was, for her, the ultimate in happiness, the sheer delight to be with her family and share a happy moment.

.jpg)

My mother was a first generation American. Her parents, Tillie and Bernie, were born in Austria and arrived in the United States just as World War I was coming to an end. Just prior, Grandpa Bernie had been conscripted into the Austrian army where he lost a brother to the war. Later, both of his parents and remaining siblings were victims of the Holocaust.

My mother’s family settled in the Bronx, where she later caught my father’s eye at the beach on City Island in the Bronx. As a very young child, she had lived through the Great Depression, which, I am certain, shaped her views on the importance of security and the value of having just enough.

Throughout her life, my mother’s tastes were simple. She was appreciative of what she had, her nurturing impulses far more pronounced than any desire for material acquisition. Perhaps if she grew up in a different era, the ratio may have been more balanced. But I suspect not, as the fulfillment she experienced from giving was so much more than any pleasure she may have felt in receiving.

As a pre-teen and into my late teens, I had the good fortune of working with my mother, not just in one job, but in two. Beginning when I was about 11, I spent a couple of summers working in my father’s cafeteria-style restaurant delivering lunchtime orders. Located in the heart of the New York City garment district on Eighth Avenue and 36th Street, the restaurant was sprawling, with two floors of seating accommodating up to 500 diners.

My mother was usually tucked away in a back office on the second floor, managing the books and ordering food and supplies. But during the lunch-time rush, from about 11 to 2 each day, she moved to the small workstation adjacent to the cashier to take lunch orders from local businesses over the phone. My mother simultaneously organized our routes and dispatched the other delivery guys and me with the boxes and bags of food.

The restaurant averaged well over a hundred delivery orders every weekday. During the lunch rush, the phone was relentless. My mother would routinely have two or three callers on hold while taking orders, never getting rattled. I remember vividly that when I got an unusually big tip, like 75 cents, or on an exceedingly rare occasion, an entire dollar(!), I would rush back to the restaurant and giddily hold it up for my mother to see. In her professional order-taking-phone-voice, she would politely ask the caller to “Please hold for one moment.” Then, turning to me, with genuine wide-eyed excitement, she would give me an enthusiastic, yet appropriately hushed, shout of “Hooray for you, Barry!”

Mr. Weiner was the full-time delivery person. He was diminutive, probably in his 70s, and he wore a suit and tie every day topped off with a gray houndstooth fedora. I never saw him without that hat! Mr. Weiner rarely spoke and never smiled. Early on in my delivery tenure, my mother explained that she gave Mr. Weiner the orders closest to the restaurant as well as those for customers known to have been generous tippers. At the end of his shift, as Mr. Weiner exited through the revolving door onto 36th Street, my mom would frequently and discreetly hand him a bag filled with food for his family’s dinner.

The restaurant closed in the early 1970s; with huge increases in NYC commercial rents, its large size rendered it no longer sustainable.

For the next year or so, my mother held a secretarial job at a funeral home a short walk from our Queens apartment. After that she was hired by a social service agency in NYC as the administrative assistant to one of the executives. She arranged for me to work in the mailroom during the summer following my high school graduation.

The main floor of the agency’s offices was bright and orderly, with dozens of white-collar workers at their desks, writing reports, holding meetings, and conforming to the dress code of the day: suits for men and dresses or pantsuits for women.

At the far end of the floor, just off the center aisle, were double doors that opened into the mailroom. Upon entering, you felt like you were in an entirely different universe. It was a hectic environment with stacks of mail everywhere, waiting to be sorted and boxed, labelled, and placed on carts for delivery. While the office atmosphere was cerebral and calm, a staid culture of civility and formality, the mailroom was physical and kinetic, an earthy culture with street language the normative communication style. The mailroom had no chairs, just a few stools placed randomly about if one got that rare opportunity to rest for a moment.

The mailroom had a distinctive smell, a potent mix of sealing tape, cardboard, and glue. There were seven of us working in this loud, frenetic atmosphere, culturally light years away from the decorum practiced with utmost care just on the other side of the double doors. When she wasn’t working through her lunch hour, my mom and I would eat together. On the other days, I ate with the guys.

On the first Friday afternoon of my summer assignment, Lance, one of the mailroom guys, motioned for me to follow him into a service stairwell. It was way in the back of the mailroom, past the mountains of publicity brochures, boxes and boxes of envelopes of every size and color, and hand trucks for transporting the heavy packages into the freight elevator.

Lance gingerly opened the large metal door, attempting to keep its creaking to a minimum. There, sitting on the steps, I discovered the rest of the mailroom crew smoking marijuana. As I entered, Bobby, whose job was boxing mailings, put his arm around me and passed me a joint, welcoming me to the club. This was a big deal for me. Not the marijuana part, but that I felt accepted by the full-time guys. One of the guys good-naturedly reminded me not to tell my mom, explaining that none of the staff on the operations side was aware of their Friday afternoon “R&R.”

Later that afternoon, I had to collect some materials from the executive office area for a mailing. I said “Hi, Mom,” as I passed by her desk.

She looked at me, a knowing smile coming to her, and said, “From the look of your eyes, I guess the guys initiated you into their Friday group.”

I was mortified, but only momentarily, because she then said, “Congratulations,” adding with a wink, “But just don’t get too carried away!” So much for the group’s big secret.

I learned something about my mom that day. Well, maybe not learned, but came to appreciate more fully as I was transitioning into adulthood. The mailroom guys loved my mom, and it was easy to see why. She was always respectful and friendly, interacting with them the same way she interacted with the executive staff. Not everyone treated the mailroom crew as she did. Some spoke in condescending tones, attempting to conceal their unconscious bias with an affect that was transparently patronizing. I came to realize that the mailroom guys accepted and trusted me in large part because of how they felt about my mother.

As the years went by, I became increasingly aware of just how fortunate I was to have Sylvia for my mom. She and my dad, George, were always so involved in our children’s lives, frequently driving up from Florida and staying for a few weeks. They loved attending the kids’ recitals, plays, birthdays, basketball games, and graduations. Amy adored my mom – she could never relate to friends who complained about their mothers-in-law.

I cannot recall once, ever, that my mother offered advice without being asked. She was acutely respectful of boundaries, delighting in doting without calling attention to herself. The lessons from observing her over the years – her warmth, her encouragement, her respect – seep in slowly, over a lifetime. I may never achieve the grace, purity, and spontaneity that characterized her caring manner, though I have come to see it as aspirational, a North Star.

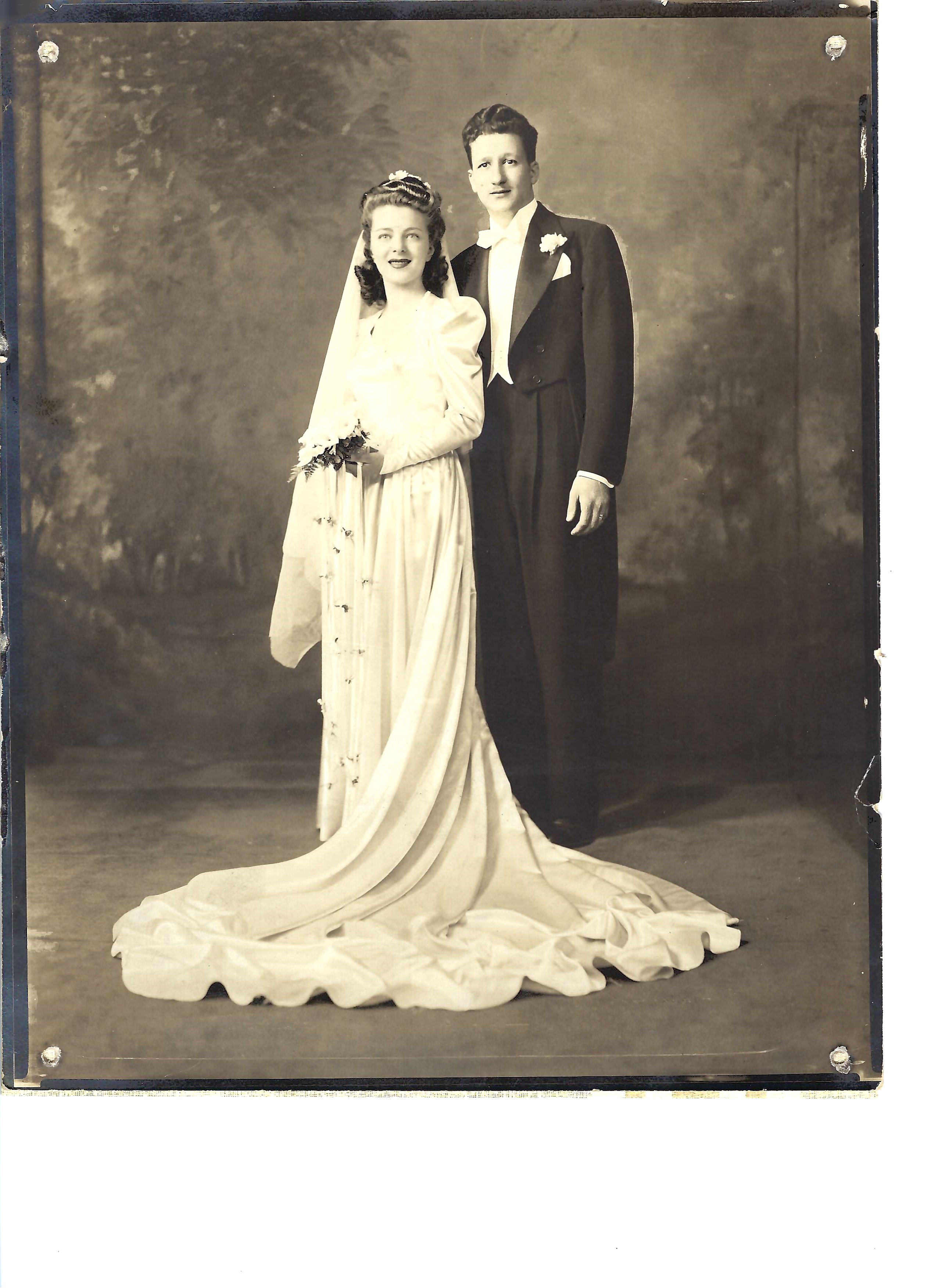

My parents had a wonderful marriage of more than 50 years, bound by a deep and abiding love that strengthened year after year. When my father died twenty years ago, it was a terribly painful blow to all of us. My

brother Larry and my sister-in-law Zipi, their kids Corinne and Michael, my sister Roberta and her son Jamey, Amy and our kids, Kerry, Jesse, and Hallie, all came together to mourn my dad and support and bolster my mom. She was the one who carried the heaviest burden of sadness, who clearly would miss my dad deeply and daily. Roberta and Jamey were still living with my mom, and it was a great comfort for all of us knowing they were there and that she was not alone.

Prior to my father’s passing, I spoke with my parents once a week, occasionally twice. But after he died, I called my mom every day, usually around 5:30. I started this practice with the thought that it would be consoling for my her. But I soon discovered that speaking with her each day was as important for me as it was for her.

Our daily conversations revolved around the details of her day, and I shared highlights of mine. The frequency of conversations allowed for the exchange of those ordinary moments that, when taken together, constituted the fabric of our lives. I enjoyed hearing her giggle about winning a lottery-sized three dollars playing cards with Pearl and Esther. I loved hearing that she had a great day at her job, a daily three-hour stint making phone calls soliciting used clothing donations to benefit a veterans’ organization.

In 2004, just a year after my dad died, my mother suffered a stroke while driving home from some errands. We’ll never know how, but she miraculously managed to drive back to her house and even navigate the car into the garage. Roberta discovered her sitting in the car, practically unresponsive.

My mother was hospitalized for several days, and we were devastated to learn that her speech and swallow function might not fully return. On one of her early days in the hospital, Jesse called her from London where he was working, just to tell her he loved her. While on the phone with him, her speech was somehow distinct, virtually flawless. But once off the phone the aphasia instantly returned. He called her daily, and we were all shocked that this miracle recurred each time. The brain can be such a mystery!

Slowly but surely, in the months to come, thanks to a wonderful team of respiratory, speech, and physical therapists, much of my mom’s functionality was restored. But not all. From then on, she remained a tad self-conscious about an inability to come up with the desired word to express her thought. She would hesitate, smile, then mentally regroup, searching for a substitute. Though she would always remain positive and cheerful, her confidence when speaking remained forever diminished.

After her stroke, I visited more frequently and made it a point to always be with her on her birthday. The first time was to be a surprise, so I rang the bell and waited on the doorstep. She was thrilled to see me standing there and I was thrilled to be there. Every year thereafter, I flew to Florida on her birthday, often with Amy and whichever of our children were able to accompany us. And each year we planned for it to be a surprise. Although she knew we were coming, and we knew that she knew, the anticipation of exactly where and when we would show up made it a fun tradition.

As I’ve written before in this space, in 2011, our family suffered a devastating loss. My dear brother Larry and my wonderful sister Roberta passed away, just four months apart from extended battles with cancer. No parent should outlive their child, no mother should live that trauma.

Even though we spoke daily and saw one another frequently, to this day, I can’t get a handle on how my mother processed the experience of losing not just one, but two children. And two children with whom she was exceedingly close, one with whom she lived and the other with whom she also spoke daily. She was fully involved in both of their families’ lives.

Where did she put the pain? I’ll never know. Amy and I had hoped that she would come to live with us. We built a bathroom adjacent to our guest room on the first floor of our home to make it private and comfortable for her. But, her life, her friends, her doctors, and home were in Florida. She may have worried that if she moved in with us, her ease of mobility would lessen. But I also sensed she thought that her presence in our home would inhibit our activity, despite our assurances that not only would that not be the case, but that we genuinely wanted her. She considered coming, but ultimately opted for her independence, which she relished.

In the days following Roberta’s passing, we gathered in Jamey’s home for a few days of mourning. He and his wife Alison always welcomed her with open arms. Upon returning to her house later that week, we discovered that the house had been burglarized. Traces of the thief were all over the place. Broken glass, dressers emptied, furniture turned upside down. My mother didn’t have much by way of material value. What she treasured most were the memories made in that house. It was heartbreaking to think that this experience might tarnish those. But my mother said, “After those we’ve just lost, the things that were stolen mean nothing. It’s time to move on.”

Amy and Jamey packed up her home, found a lovely apartment in a nearby senior community, where she already had friends and seamlessly moved her in. (I had just had orthopedic surgery, the result of a quirky accident, and was unable to fly down to help.)

My mom quickly felt at home, resuming her social activities: playing cards and mahjong and attending shows at the clubhouse. We continued to speak daily. Her favorite TV show was Dancing with the Stars, so Amy and I began watching so we could all share our thoughts about the contestants’ performances. Jamey, Alison, and their first son Ronen doted on her, including her fully in their family life.

For her 90th birthday, we rented a lovely space in a country club, invited about 40 relatives and friends, and celebrated with a luncheon. Speeches were on the agenda during dessert. My mother sat poised in a chair in front of the room, and I sat beside her. One by one, people shared memories of their times with her. They all spoke so lovingly.

Our daughter Kerry dressed up her pup Krishna in a tuxedo for the big event. In front of the group, she asked, “Grandma, you would do anything for me, right?”

“Of course,” my mom agreed. “Anything!

“I know you are not a big lover of animals, but since you would do anything for me, please give this handsome young guy a kiss,” she said pointing to Krishna.

My mom laughed heartily and complied to a round of applause. I was reminded of how often I would see the two of them laugh together over the years.

Next, her sister Lil and brother Marvin recalled childhood memories of their favorite foods, the unresolved fate of a treasured doll that disappeared one day, and the foibles of their parents. My mother’s friends talked about how much they cherished her friendship.

My mother sat, listening, smiling. But I could sense a hollowness, the wistful look in her eyes the giveaway. It was, I understood, a complicated mix of appreciation and longing, missing her beloved husband and precious children. She held my hand during all the speeches, appreciating me, I’m sure, for me alone, but also because I was the only remaining member of our immediate family. For a person whose emotional constitution was built on family, how bittersweet this event must have been for her. At one point, she turned to me and said she loved me and that “it’s just us now.”

The gathering of family and friends was overflowing with the outpouring of love for my mom, yet it was a painfully poignant affirmation of those who were not there, those so sorely missed.

My mother held onto her life as best as she could, desiring to preserve her independence with the dignity that such autonomy afforded. At first, she was uncomfortable about the need to use and pull around an oxygen tank. But she soon embraced it, joking that she was walking her pet. She was a humble person but was immensely proud knowing that she could be a source of strength, love, and joy to her family, never a burden. When she spoke of family, and she did often, it was always upbeat and with a smile.

Right around New Year’s Day 2015, my mom’s health took an abrupt turn. Breathing went from a challenge to a struggle, seemingly overnight. She was admitted to the hospital and was connected to a stronger oxygen delivery system.

I flew to Florida and was distressed to see the staggering extent of her decline. I wasn’t ready for her life to come to an end. I suppose we never are with those we love. After three days, I returned to NJ, and Amy and Hallie, our youngest, came to spend a few days. Our plan was to alternate visits. I was to return on the day they would leave.

One evening, while Jamey was sitting next to her hospital bed, she lifted the oxygen mask from her face and weakly, but firmly, whispered to him, “I have no regrets.” She knew the end was nearing, and she wanted to reassure Jamey that she had come to terms with it. This was her way of comforting him.

Earlier that same day, she told Amy and Hallie that she would like to go home. It took a day, but Amy and Hallie arranged for home hospice care workers, an ambulance, and for her apartment to be outfitted with a hospital bed, an oxygen system, and all the other necessities for someone in her condition to be cared for at home.

The next evening all was in place and some of the floor nurses came in to say goodbye. They had come to know her over the years and were sad knowing she would likely not return.

Hallie accompanied my mother in the ambulance and Amy followed in the car. As the ambulance pulled into her development, the driver asked which building to go to. Before Hallie could respond, my mom pulled the mask away and said “Building C.” The driver and the attendant chuckled and had instant respect and admiration for her and treated her so carefully and so kindly.

I had already arranged a flight down for the next morning. My packed suitcase was sitting at the door. Zipi visited my mom, giving her a warm hug. Jamey was in and out all day.

Amy and Hallie kept vigil all night, talking and singing to her, wanting to spend every possible moment with her. At about 4 in the morning, Amy suggested to Hallie that she try to sleep for a bit. Hallie, who was fiercely devoted to my mom, as were all her grandchildren, reluctantly agreed.

Amy then sat, holding my mom’s hand. At one point my mom reached up with both arms extended and smiled. Amy said it seemed like she was seeing love – maybe my dad, maybe Larry, maybe Roberta, maybe her parents. Maybe it was all those she loved who were missing from the birthday party. I didn’t get there in time to say a proper good-bye, but she knew I was on my way. Maybe that smile was for me as well.

Maybe she smiled because she indeed, had no regrets. A life well lived.

She lowered her arms and took a breath. A peaceful, final breath.

My mother’s most precious gift to me was making me feel good about myself every day and loving me unconditionally. What greater gift can a parent provide a child? When I think of her, as I so often do, I see her beaming, just as she did each time I prepared to jump into the pool.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This was the last video I have of my mom, taken just a few months before she passed away. I had gone to visit her in Florida and asked her to say a few words to those back home: 20140707_172323.mp4 (dropbox.com)