Shoes of Despair, Shoes of Hope

The three students, around twelve or thirteen years-old, stood awestruck, silently staring at the shoes, hundreds of shoes, haphazardly heaped together. This was no ordinary collection of shoes. All were about 80 years-old and deeply weathered, their cracked brown leather preserved in their uncleaned and fraying state, their rigidity diminished from the passage of time and the weight of the mound. Some were low-top boots, some women’s pumps, but most were nondescript and undistinguishable as belonging to one gender or another.

After a moment, one of the students expressed precisely what the viscerally charged moment called for, saying as much to himself as to the others, “I can’t believe actual people wore those, walked in them.”

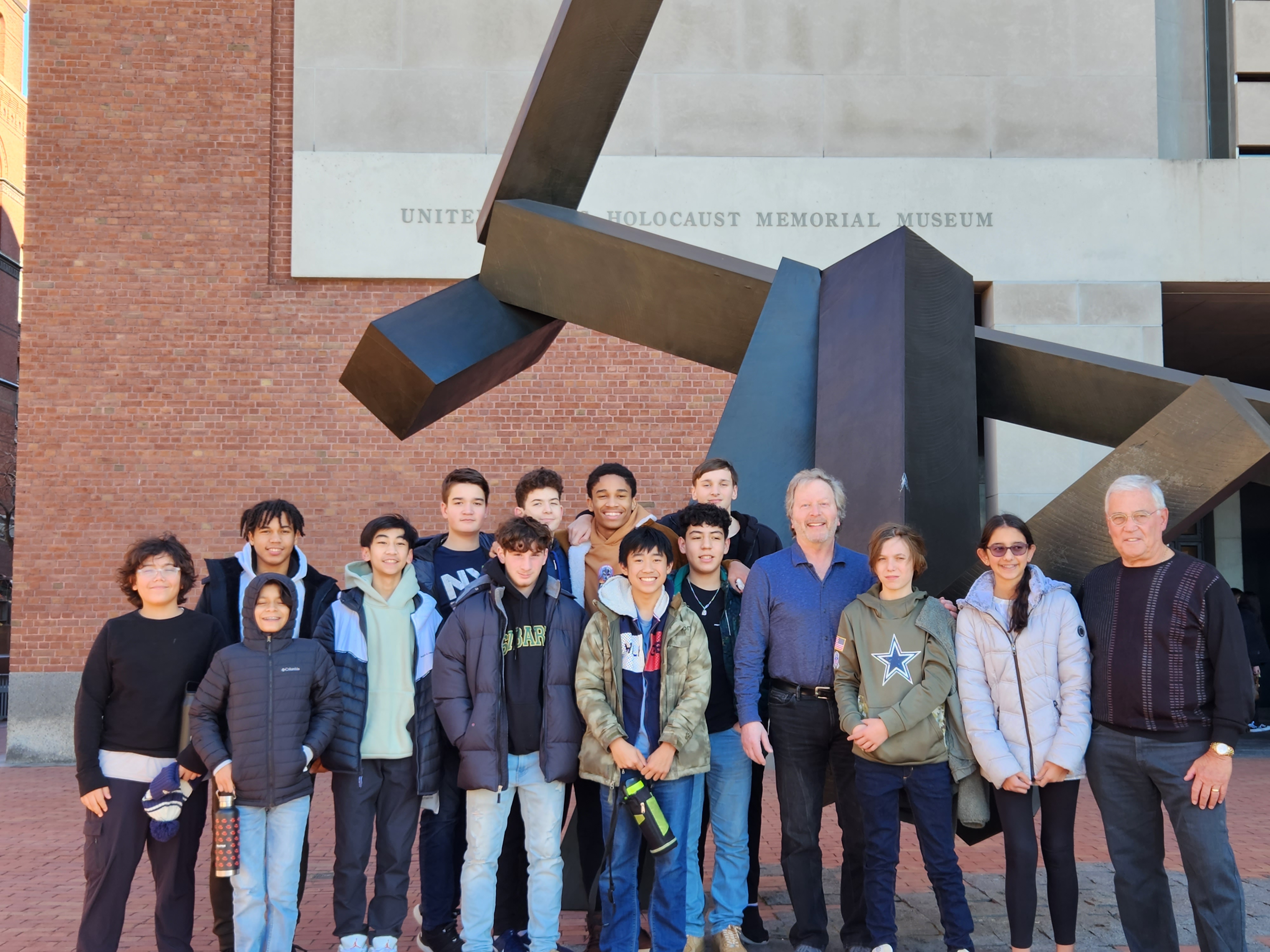

The shoes drew them into a moment in which their different religions and backgrounds were transcended by a common sense of shock and sorrow, a moment in which they were brought face-to-face with the unimaginable toll that hate and racism can exact. The pile of shoes was on display at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. where I had the privilege of joining an interfaith student excursion last week, fittingly held on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

From a distance, and not even that much of a distance, the pile of shoes looms as a large mass, a seemingly unremarkable mound of tattered leather undivided into discernible objects. A big brown blob, formless. It’s like looking at a forest from the sky and seeing only a wide expanse of green.

Until you get closer.

As you make your way toward the pile, the more each individual shoe comes into focus. The whole gives way to its constituent parts. Your eyes drift across the mound. One shoe catches your eye, then another – a metal eyelet emerging from the dark mass. A chipped heal. A ripped lace. A shriveled tongue. A shoe that that had become so flattened that it was impossible to tell if it was for the right foot or the left. A small shoe, surely a child’s, catches my eye; the hole in its sole must have begun as a tiny crack but grew so large that it undoubtedly failed to protect its wearer’s young foot from rain and snow, from the frozen ground.

And of course, you wonder, with each, who walked in this one? Who trudged through slush and ice in that one, the one with the detached heel?

As much as I was drawn to the exhibit, I was drawn to the students’ reactions. I looked at their faces. It may have dawned on them that any one of those shoes could have been worn by a teenager, the same age they were – a teenager whose life may have come to an end just moments after removing those shoes, perhaps their very last act before the deadly combination of viciousness and hatred sealed their destiny.

In some ways the shoes were emblematic of the people who wore them. Ripped from their mates, discarded, robbed of identity, left to rot in a heap. But unlike those who wore them, the shoes may have been seen by the Nazis as having some worth, the leather potentially repurposed. Old worn shoes of greater value than the human beings who once wore them. For the students on the trip, this was a cold, hard reality and they were taking it in.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum helps visitors to experience the Holocaust through two lenses, the macro to gain a sense of the enormity of the horror, gruesomeness on a scale that ought to defy imagination, and the micro which brings one into the highly personized space of individuals, real people with life stories, families, hopes, dreams. As one display noted, the Holocaust was not six million killed, it was one person killed six million times.

The group I accompanied was organized by the Daniel Pearl Education Center, part of Temple B’nai Shalom in East Brunswick, NJ, which has been conducting this trip for many years. To their great credit, they bring students from different faiths, including from a local Catholic school and, when feasible, from local mosques. To ensure the trip is meaningful and enriching for all, my good friend, Dr. Andy Boyarsky, who chairs the center, does extensive planning with the Daniel Pearl committee members, including Rebecca Brenowitz, Danny Gresack, and Sharon Roach, as well as Rabbi Eric Eisenkramer, along with Father Timothy Eck, Principal Theresa Craig, and Terese Maligranda from the Saint Bartholomew School.

The Museum houses a permanent exhibit which is displayed across four floors and is organized chronologically from the Nazi takeover of Germany in the 1930s on the top floor to the aftermath of the war on the first floor. Visitors begin the tour on the fourth floor and make their way down on a self-paced basis.

Upon our arrival, Jordan Tannenbaum, the Museum’s Chief Development Officer, met our group in a large hall, its walls adorned with children’s artwork portraying what the Holocaust meant to them. Jordan provided an orientation, and his endearingly avuncular presence comfortably prepared the students for what lie ahead.

Spread above the multiple panels of the artwork is a quote from Yitzhak Katzenelson, a Russian-born poet who had been imprisoned in Auschwitz where his wife and two of their three sons were killed before he and his remaining son met the same fate. The quote, taken from his elegy, The First Ones, captures the notion of death and rebirth, precisely the theme of the Museum: “The First to Perish Were the Children…From These a New Dawn Might Have Risen.” As I watched the children listening attentively to Jordan’s description of the artwork, I couldn’t help but think that these children were part of the new dawn; they were about to begin a journey where they would learn about those who perished.

We were all taken by elevator to the fourth floor. The scene we encountered upon exiting the elevator was starkly somber and disturbing. Through artifacts, film, photos, and scaled models of the camps, the exhibit captures the systematic way in which Nazi brutality was employed to stigmatize, marginalize, ghettoize, and terrorize, progressively building toward the Final Solution, the massive and systematic program designed to wipe out the Jewish population. The students see it all – the Nazi symbols, swastikas everywhere, the menacing cold steel weaponry, Jews forcibly removed from their homes, all the grueling harshness of ruthless destruction.

The third floor focuses on the early stages of World War II, depicting both the expansion of the war and the institutionalization of genocide. The construction of the death camps, intended not just for Jews, but for prisoners of war, gay people, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Roma, as well as other marginalized groups, is hauntingly laid bare. It is an astonishingly horrific story brought to light through recorded testimony, video, photos, and models. The students stared, mouths agape at images of prisoners, emaciated, naked, stripped of their clothing and their dignity, forced to dig their own graves. As they walked through the exhibit, the students’ stunned silence spoke volumes.

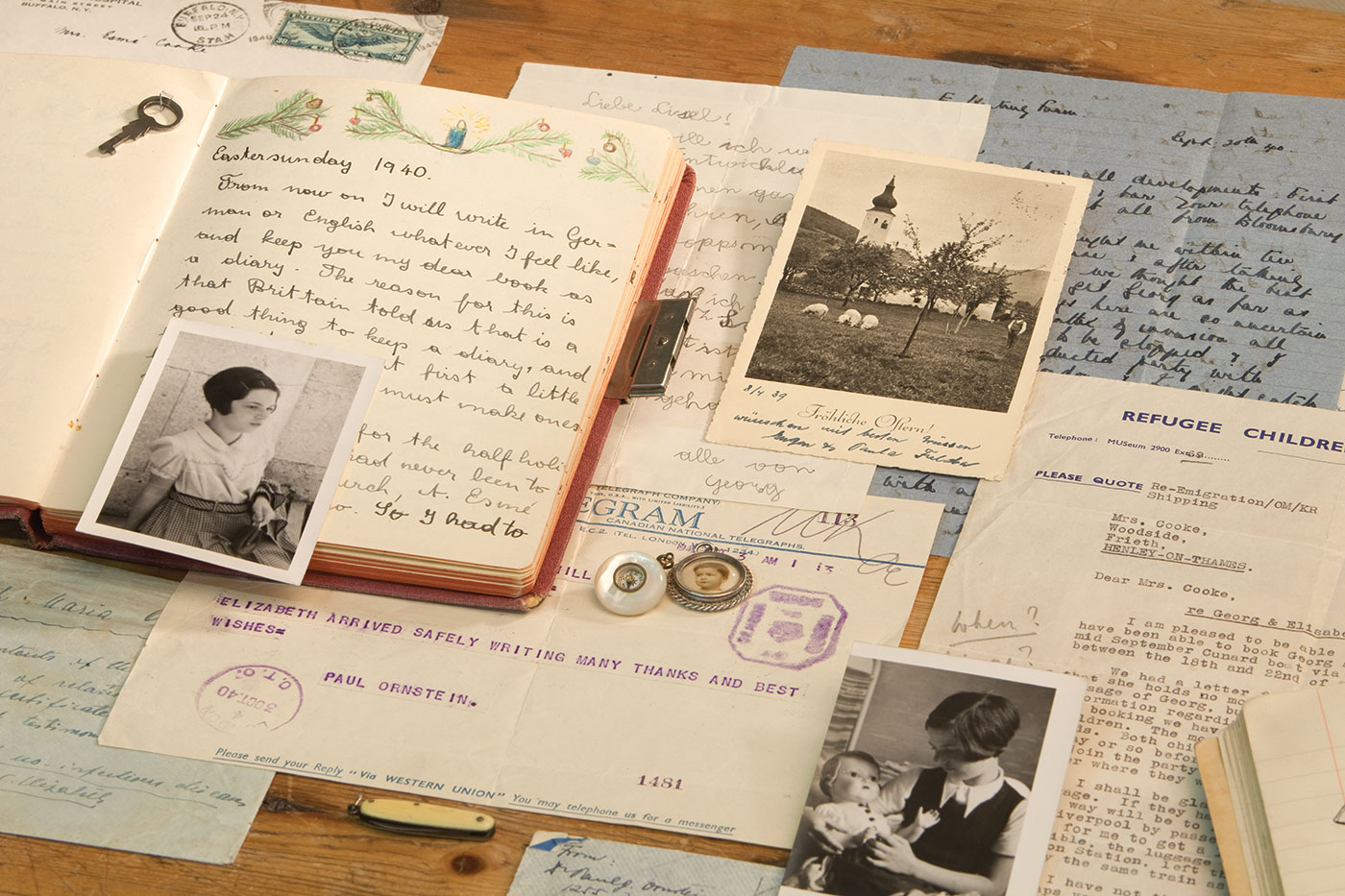

The Museum personalizes the experience with photos and stories of Anne Frank and so many others, allowing visitors to look into their eyes and hear the voices of real people who suffered through indescribable persecution.

I walked over to two students riveted on the photos and writings of Anne Frank and asked if they were familiar with her. One said yes, the other shook her head no. The student who knew of Anne Frank said she hadn’t realized she was so young, the same age as she was. The other student, who appeared to be about 12, looked up at me and said, “I just can’t believe all this. How could they do this to a kid?” Their faces had a bewildered look, a telling indication that nothing in their life experience had prepared them to make sense of this.

As the group made its way down to the two final floors, they encountered more explicit photos, more heart-rending stories, more evidentiary relics. A group of six or seven students were huddled around a small exhibit, a short film depicting experimentation on unwilling concentration camp prisoners. The students were mesmerized and horrified by the graphic images of brains being probed, skin mutilated. For these young people, this would be the world of science fiction. But maybe not really, as the scenes they were watching took inhumanity to a hell even science fiction typically dares not go. Yet, it was real. Real people exercising incomprehensible barbarism on other people. For a minute or two, the students watched the film in silence. Then one leaned toward the other and said in a shaky voice, “How could this happen?”

“How could this happen?” I heard versions of that question throughout the day. Then, toward the end of the tour, I overheard one young girl ask her friend, “Why didn’t they stop it?”

The great irony is that those questions – “How could this happen?” and “Why didn’t they stop it” – are inextricably linked. The very people who directly committed those atrocities were ordered to do so by those holding positions of authority, the group these kids have probably grown up to believe are the ones in charge of stopping bad things from happening, those on whom we depend to intervene on behalf of sanity, rationality, humanity. But now they were exposed to the grim truth that things don’t work that way all the time.

Following the tour, we assembled in an auditorium for a presentation from Dr. Rebecca Carter-Chand, the Museum’s Director of Programs on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust. The theme of her talk, which was masterfully tailored to this age group, was on distinguishing between crimes of commission and omission. As she explained to the students, we have a keener sense of what active wrongdoing looks like. Much of what they observed on the tour was exactly that, overt criminality. But she planted in them the notion that standing by when a wrong is committed may also be considered a crime. Dr. Carter-Chand gave examples of how some in the church as well as other societal institutions added their voice and resources to stop the genocide, while others in the church and other institutions either did too little or nothing at all.

On the bus ride back to New Jersey, the students were invited to share their impressions of the day. A few students expressed confusion as to how people could stand by while this nightmare was unfolding. One or two students spoke about how the Nazis tried to legitimatize killing with a science-sounding rationale, that is, in declaring Jews to be racially inferior the Nazis were doing society a favor by eliminating the race. This fraudulent co-opting of scientific vernacular is certainly not new. Such practice has been used throughout history in the service of dehumanization, providing the justification to seize territory as was done, for example, by early Americans to Indigenous People, imposing slavery as was done to Black People, and separating citizens from the rest of the population as was done to those of Japanese ancestry who were forced into internment camps during World War II.

A couple of students spoke about the shoes. One poetically observed that shoes take us on the path of life, and the wearers of the shoes in the exhibit were cut off from their paths.

Presumably, the day siphoned off some of the students’ innocence. But a fundamental question is, what replaced it? Cynicism? Mistrust? Despondency? Anger? Those would surely be understandable, particularly in a world in which divisiveness and hate have taken too strong a hold in how we see others who are different from ourselves. But those reactions were not the thrust of what I observed that day. Rather, judging from the students’ feedback, that little piece of innocence lost was replaced with reflection, thoughtfulness, and undoubtedly, as time goes by, wisdom.

For the students, that may translate into a budding belief that it’s not just those in authority, and not just adults, who have responsibility for keeping hatred from poisoning society. Rather, such responsibility lies in all of us. And when the students experience that realization communally, with those of different backgrounds and different faiths, the foundation is laid for them to do their part to protect all from prejudice, and not just those who look like them or come from the same communities.

What’s more, as that foundation of thought blossoms, it can give rise to the conviction that differences should not be merely tolerated, but that they should honored, respected, and even celebrated, because it’s by examining the world through different lenses, different perspectives, that we learn and grow.

It is necessary to study genocide, wherever it occurs and on whomever it is perpetrated, because we are morally obligated to understand and prevent it. But it is also important because it can spur our imaginations to more fully understand and value others who are different from ourselves, to embrace those differences with kindness, curiosity, and love. To see others as they would have us see them.

We can begin by asking those who are different from ourselves, with an open mind and generous heart, what it is like to walk in their shoes.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

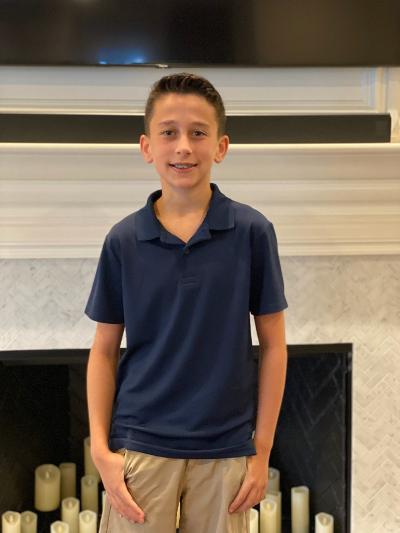

Postscript: On the weekend following our visit to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Amy and I attended our great-nephew Jayden’s bar mitzvah in Houston. As part of his bar-mitzvah project of giving back, Jayden has been spending the last several months collecting and distributing new or gently used shoes to children in a nearby underserved community. Shoes! I had been thinking about shoes all week, not only about the horrific imagery of the shoes discarded by people being herded toward their death, but also, as expressed so movingly by the student on the museum tour, that they protect us as we walk on our life paths. It was so heart-warming to learn that Jayden is doing his part to help those less fortunate to continue on their paths. Shoes of Hope!