Vincent Van Joe

My father-in-law, Joe Fishman, passed away last year, three weeks after his 96th birthday. This is his birthday month, and his was a life worth celebrating. Joe worked his way up from a mechanic who serviced large industrial printing presses to become the company’s national service manager. He dabbled in carpentry and art from the time he was a young man. He loved to paint the great masters, favoring Gaugin and Van Gogh, but he took the greatest pride in the frames he built for them. In his later years, he also learned how to create stained glass art. We have some of Joe’s art in our home, but one painting especially stands out, although it almost got Amy and me into big trouble.

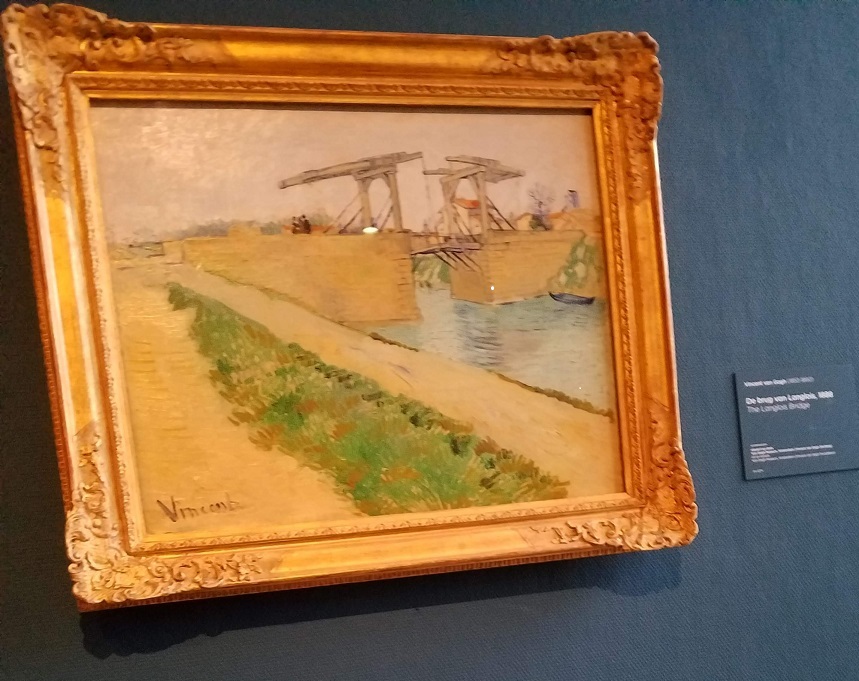

When Amy and I moved into our first house, Joe gave us a painting that he had made when he himself was a young father. Amy grew up loving that painting and was so grateful to have it in our new home. Joe explained that it was a reproduction of one of four Van Gogh oil paintings of Langlois Bridge at Arles. He had signed it “Vincent,” in the same lower left corner of the painting and with the same signature style as the original. He jokingly referred to it as his “Van Joe.”

A couple of years ago, Amy and I were invited to present papers at a conference in Brighton, England. Thrilled at the opportunity to visit Europe, we also planned a few days in Amsterdam. There, we strolled along the canals, tasted their iconic – and incredibly delicious – caramel-filled wafers called stroopwafels, and visited a few of the many museums.

As we exited the elevator on the second floor of the Van Gogh Museum we walked straight ahead, and there, to our amazement and delight, hanging in a corner of one of the large rooms, was the original Langlois Bridge at Arles! We were so excited that we forgot their strict “no photos” rule and took out our phones for selfies in front of the painting. Seemingly from out of nowhere, a foreboding security guard swooped in, sternly reminding us of the rules. I tried to explain the personal significance the painting, but she wasn’t having any of it. She glared as I put my phone back in my pocket.

Of course, we shouldn’t have pursued the picture-taking. Aside from wanting to be respectful, we were concerned about reinforcing the stereotype of “entitled” Americans believing the rules don’t apply to us. On all relevant grounds, it was the wrong thing to do.

And yet…

We reasoned that this was no ordinary circumstance, that we had a higher purpose in mind: a desire to show Joe that we were in the same room as the original. He and Janet, Amy’s stepmom, had been in that very spot decades ago and it felt important to show him that we were literally following in his footsteps.

Thus, the challenge was on!

Under the watchful eye of the guard, we began to amble away, side-eyeing her the whole time. Believing her work with us was done, she shifted her attention to other infraction-committers… the singing child whose glee was too much for the guard to bear… the young man expressing his fascination with a Van Gogh self-portrait with a close-up lingering stare that she found irksome.

We lurked nearby, hoping for even the briefest opportunity to take a picture. The guard’s route across the gallery followed a pattern: down a center path, crisscrossing from wall to wall on her return trip. We observed as she made two passes back and forth, her pacing deliberate.

The guard again neared our target, stood for a second, then pivoted and headed away from it. This was our chance. Amy and I walk-ran to the corner. With my phone concealed in one hand and held about waist high, I took a series of photos in quick succession, hoping the camera was pointed properly toward the painting.

Click, click, click, over and over. I didn’t know how many photos I had taken. I took as many as I could in the three or four seconds I had before the guard might look our way. For all I knew, I had taken 50 shots of the ceiling or the floor, or photos of strangers’ shoes. Or dozens of knees.

We scurried to the lobby of the museum to check. Success! Two of the photos came out as well as could be, well, at least under the circumstances. The rest were, yes, shoes, ceiling, and floor tiles, and some of empty wall space between paintings.

Joe laughed at the story of our Amsterdam photo exploits. He was touched by our effort, and his obvious enjoyment validated our belief that our transgression was worthwhile.

When I look at the painting today, the centerpiece of our fireplace mantel, I am reminded of how kind and generous Joe was to his family. Many years ago, he and I spent the weekends of an entire summer building a wall unit for our Queens apartment. Joe was a master at carpentry, and the wall unit was quite intricate, with carved racks to hold wine glasses and a fancy fold-down bar shelf. I learned much from him.

But more than the big projects, it’s the million small kindnesses that, when taken together, add up to a very caring, giving person. Van Gogh said, “Love many things, for therein lies the true strength, and whosoever loves much performs much, and can accomplish much, and what is done in love is done well." Joe, indeed, loved many things and accomplished much. And he was certainly loved by many as well.

The painting of Langlois Bridge at Arles has always occupied a special place in our home and our hearts. Now, it has become a part of Joe’s legacy. How fortunate we are to have had him in our lives, and how fortunate to have this wonderful reminder of him and his creative passions, our own unique “Vincent Van Joe.”